As Zambians debate Bill Seven, questions grow over whether the “public input” behind it reflected genuine citizen voices, or carefully arranged support. Chipata’s public hearings reveal a troubling gap between the government’s promise of inclusive reform and the reality of a tightly managed process.

By MakanDay and the team of five journalists in Eastern Province

Zambia’s contentious constitutional reform initiative, widely referred to as Bill Seven, has returned to Parliament after a court-ordered halt — but the journey it has taken reveals a much more complex picture.

Its reintroduction has reignited public debate, with some civil society organisations, church groups, and opposition parties warning that the process is being pushed through too quickly and without genuine citizen engagement.

The proposed changes to the Constitution include increasing constituency-based seats from 156 to over 200 seats, introduce reserved seats for women, youth, and persons with disabilities, introducing a hybrid voting system, and raising the number of presidentially appointed MPs from the current eight.

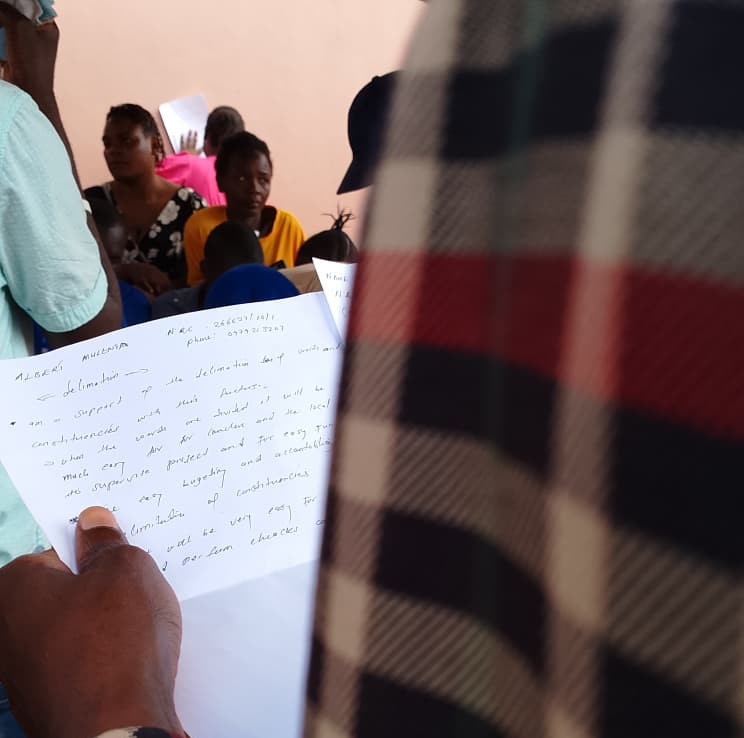

In Chipata, Eastern Province, where ordinary citizens were invited to help shape the country’s supreme law, MakanDay and a team of five local journalists documented a consultation process that looked inclusive on paper but unfolded very differently on the ground. The team gathered videos, photos and interviews with some of those who were ferried to the venue.

Buses arrived carrying mostly youths and women, many unsure why they had been called. Submissions sounded rehearsed, and long afternoon queues formed as participants collected unexplained K100 allowances.

What should have been genuine civic participation instead exposed a process vulnerable to political mobilisation, poor communication and subtle manipulation, casting doubt on the legitimacy of a reform effort the government insists is citizen-led.

It remains unclear why Chipata became the focal point for this level of engineered support. No similar reports emerged from other districts. In Kasama, northern Zambia, for instance, a journalist who covered the hearings there described the process as smooth and largely free of interference.

A consultation already under strain

Early sessions in Chipata drew low turnout, with many residents, especially youths, unaware the consultations were happening. Attendance surged midweek when alleged ruling United Party for National Development (UPND) officials began ferrying groups to the venue for what appeared to be arranged submissions.

On 31 October, President Hakainde Hichilema encouraged citizens to support the review, arguing that more constituencies would enhance representation. His remarks coincided with a sudden wave of pro-delimitation submissions in Chipata. Inside Uncle Chipeta Lodge in Chipata, the venue of the submissions, some participants struggled even to pronounce “delimitation,” yet their support for it was strikingly uniform.

“The submissions for Wednesday and Thursday were almost identical,’’ said one of the participants. “People kept saying delimitation was good, but when asked to explain, they couldn’t. The second, third and fourth, all repeated the same points. It sounded rehearsed.”

She added that she observed participants queuing for K100 payments near a parked white Toyota Hilux.

By Thursday, mobilisation had grown more open and noticeable. Additional buses arrived, including one from Chipata Teachers Training College, carrying mostly civil servants – teachers, nurses, and support staff. Several passengers told MakanDay they only learned the purpose of the trip upon arrival.

These accounts now sit at the centre of growing concern that the hearings were rushed, poorly communicated, and vulnerable to manipulation.

Officials push back, observers disagree

In an interview with MakanDay, UPND deputy provincial chairperson Alex Phiri, named among those allegedly involved in mobilisation, denied any role in transporting participants.

“I was there almost all the days, but I never saw anyone being transported there,” he said.

But Alliance for Community Action (ACA) Executive Director Laura Miti, who observed the public sittings in Chipata, offered a sharply contrasting view. She said communities on the outskirts had little access to the process, some participants were reportedly instructed on what to submit, and others were mobilised simply to boost numbers.

“So overall, the sense is that its technical committee really was window-dressing, practically, was really difficult to get a good view of what Zambians really want,” she said.“In our view, as the ACA, it wasdesigned to ensure that Bill 7 as it was, would pass. So, it was more of a clean-up exercise.”

Inside the mobilisation machine

MakanDay established that mobilisation began well before the public sittings. Well-placed sources said local party structures coordinated with officials from Lusaka to arrange transport, meals and allowances for participants.

Eastern Province Deputy Permanent Secretary Lewis Mwape, who was seen at the meeting held at the provincial health office on Sunday 26 October, denied convening any gathering to canvass support. He confirmed meeting some civil society leaders, including Ms Miti, but insisted he did not attempt to influence anyone’s position.

“The meeting called by Dr. Lewis Mwape did not work out because NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) were being pressured to adopt a single position, to support the constitutional amendments, particularly on delimitation and representation,” said one source who attended the meeting.

Two days later, on October 28, a second meeting reportedly involving UPND-aligned CSOs was held at Jemita Lodge, allegedly attended by a State House official and a former UPND MP. The official referred all queries to State House when approached for comment.

The constitutional framework

The Constitution mandates the Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) to delimit electoral boundaries at least every ten years, considering population, geography and social cohesion. The amendment process currently underway falls within this mandate.

Public sittings began on 27 October, with teams deployed nationwide in two phases, concluding in Lusaka from 10 to 13 November. President Hichilema had earlier sworn in a 25-member committee chaired by retired Supreme Court Judge Christopher Mushabati, tasked to propose amendments through what he called “an inclusive, consultative, cost-effective process that reflects the voices of all Zambians.”

This pledge followed public backlash against the 2025 version of Bill Seven, criticised for being rushed and opaque. Civil society pressure forced the creation of the new technical committee—welcomed as progress, but overshadowed by suspicion.

Civil society’s cautious support

Civil society and faith-based groups cautiously endorsed the review but insisted its legitimacy depended on transparency, open access to draft documents, and meaningful participation of women, youths and marginalised communities. They also warned that dissenting voices must be protected.

Governance experts say a transparent review could strengthen public trust and reshape Zambia’s governance culture. Yet the scenes in Chipata highlight how easily consultation can slide toward manipulation.

For the majority who were transported to make submissions, constitutional promises only matter when they translate into better lives. They spoke of wanting their children to have access to education, healthcare, clean water, and decent housing, not as policy ambitions, but as guaranteed rights in the constitution.

Zambia’s repeated struggles to produce a constitution that genuinely reflects citizens’ aspirations stem largely from a lack of national consensus, with recurring concerns over inclusivity, transparency and political will, according to experts.

In a 2012 interview, Professor Muna Ndulo, one of Zambia’s most respected legal scholars, warned that many African constitutions fail not because of poor wording, but because they are built on flawed, exclusionary processes.

Ndulo, who helped to draft the constitutions of South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Afghanistan, said the most successful constitutions were those in which there was a complete separation of powers between the three arms of government – legislative, executive and judicial.

“You can’t say the substance is going to be right when the process is wrong. It just doesn’t happen,” he said at the time. “You could get miracles, no doubt, but I think ordinarily those things don’t happen that way.”

The main image used in this story is AI-generated. It is included for illustration only and does not depict any actual scenes from Chipata.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.