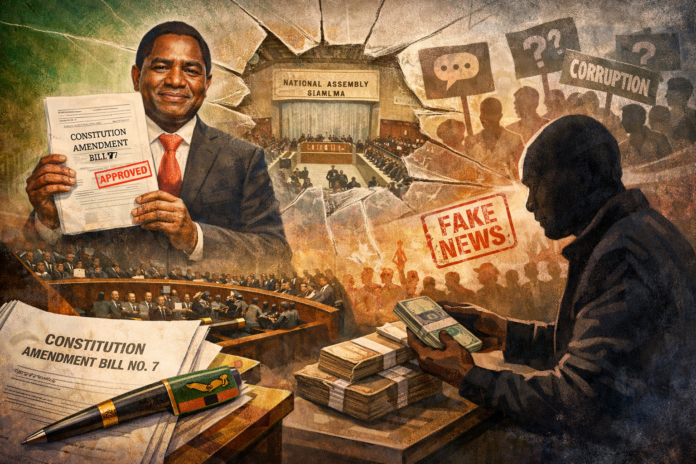

From 156 to 281 MPs, Bill Seven passed with ease in parliament but deepened public doubts about Zambia’s constitutional reform process.

By Linda Tembo

After months of heated debate, public suspicion, and sharp resistance from some civil society groups and opposition parties, Zambia’s Constitution (Amendment) Bill No. 7 of 2025 crossed its final hurdle, becoming law following presidential assent by President Hakainde Hichilema on Thursday 18 December 2025.

The Bill was passed by the national assembly on Monday, December 15, with overwhelming numerical support. At second reading, 131 Members of Parliament (MPs) voted in favour, rising to 135 at third reading, with no recorded opposition or abstentions. On paper, the numbers suggest consensus. In public discourse, however, Bill 7 has remained deeply polarising.

For government, its enactment marks a defining milestone in Zambia’s constitutional reform agenda, one it says is aimed at strengthening governance and widening political inclusion ahead of future elections. For critics, the process has raised persistent questions about transparency, power, and whose voices truly shaped the reform.

After signing the Bill at the Mulungushi International Conference Centre in Lusaka, President Hichilema described its passage as a moment that “belongs to all Zambians,” insisting that the reforms were not designed to benefit any single group or political interest. He dismissed claims that the Bill sought to extend the presidential term, remove the running mate, or weaken the vice presidency, describing such assertions as misleading and deliberately divisive.

According to Hichilema, the amendments were designed to add, not subtract, from the Constitution, particularly by expanding representation for women, young people, and persons with disabilities, while retaining the five-year presidential term limit. He acknowledged the intensity of the national debate but argued that robust disagreement, when conducted responsibly, strengthens democracy rather than undermines it.

Constitutional law expert Dr O’Brien Kaaba, a lecturer at the University of Zambia, offers a more cautious reading of the moment. While he agrees that the amendment process complied with the law, he cautions that legality alone does not resolve the broader political and democratic questions raised by Bill 7.

Dr Kaaba notes that constitutional reform should not be reduced to adjusting isolated clauses, but should be treated as an opportunity for deeper institutional renewal, one that re-engineers public institutions to be more accountable, legitimate, and responsive to citizens.

“In my view, the provision that anchors constitutional amendments is Article 79. As long as the final product complies with Article 79, then the law is fulfilled in terms of what should or should not be considered appropriate for constitutional amendment,” he said.

However, he added that whether the content of the Bill is desirable, acceptable, or politically sound is a separate debate altogether — one that remains unresolved in the public sphere.

One of the most contentious aspects of Bill 7, Dr Kaaba said, is delimitation. While the process is already provided for under the Constitution, he noted widespread concern over the lack of transparency, particularly the absence of a publicly shared roadmap outlining how delimitation would be conducted.

“Delimitation is a constitutional process already provided for under the current Constitution,” he said. “What matters is that it is conducted transparently and strictly in accordance with the Constitution.”

As parliament debated the Bill, controversy spilled beyond the chamber and into political circles and social media. Claims began circulating that some opposition and independent Members of Parliament had allegedly received as much as K3 million from the ruling United Party for National Development (UPND) to soften their stance and support Bill Seven.

Given the seriousness of the allegations and their implications for the integrity of Zambia’s legislative process, MakanDay interviewed several of the MPs named to establish the veracity of the claims.

All the MPs contacted either denied receiving any money or declined to comment. Those who responded insisted that their positions on Bill Seven were informed by their understanding of the proposed amendments and consultations with constituents, not by any financial inducements.

Patriotic Front (PF) Chama South MP Davis Mung’andu dismissed the claims as false and malicious, warning that reckless and unverified accusations risk undermining democratic debate and placing lives at risk.

Independent MP Emmanuel Banda of Muchinga Constituency similarly denied receiving any money, saying he had not received “even K500,” and questioned why his name appeared on lists circulating online.

PF Kanchibiya MP Sunday Chanda described the allegations as baseless and warned of possible legal action if evidence was not produced. PF MPs Anthony Mumba and Elias Daka also rejected the claims, urging anyone with proof to approach the courts. Isoka PF MP Marjorie Nakaponda declined to comment.

While MakanDay found no evidence of bribery, it documented a widening gap between public suspicion and the absence of proof, underscoring how deeply contested Bill Seven was, both within parliament and among the wider public.

Essentially, the Bill introduces some of the most far-reaching constitutional changes since 2016. It ushers in a mixed-member proportional representation system, combining the current first-past-the-post model with proportional representation seats for women, youth, and persons with disabilities, allocated by the Electoral Commission of Zambia based on party vote share.

It also significantly expands parliament, increasing constituency-based MPs from 156 to 266 following delimitation, while adding special seats for women, youth, and persons with disabilities, one of the largest structural shifts in Zambia’s legislative history.

Taken together, Bill 7 redraws Zambia’s political architecture. Whether it ultimately strengthens democracy or concentrates power will depend less on what is written in the Constitution, and more on how these reforms are implemented, contested, and enforced in the years ahead.

In simple terms, the amended Constitution provides that Zambia’s national assembly will be made up of several different categories of members. Most of them, 226 Members of Parliament, will be elected directly from constituencies.

An additional 40 MPs will enter Parliament through a proportional representation system, specifically to increase representation for women, young people, and persons with disabilities.

The president may also nominate up to 11 MPs. In addition to these, the Vice-President, the Speaker, and two Deputy Speakers are members of the Assembly. Altogether, this means the National Assembly can have up to 281 members.

The AI-generated image is for illustrative purposes and should not be interpreted as a depiction of any real person, action, or event described in this report.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.