As power-cuts force pupils to take their own water to school, we investigate the effect of the crisis on Zambia’s debt-ravaged electricity company

Authors | Charles Mafa and Nick Mathiason

Partner | MakanDay Centre for Investigative Journalism

In March, as Zambians continued to grapple with deep economic uncertainty – a crisis worsened by higher prices from the Russia-Ukraine war – Matthews Kachali, a councillor in Chipata, 600 kilometers from Lusaka, received more disturbing news.

At a local primary school for more than 1,500 children, pupils were having to bring water from their own homes.

The reason? Nadalitsika Primary School relies on electricity to pump water from underground. But it had run out of allocated electricity units and had not yet received a promised grant to buy more. So for two weeks, the school had no power.

“The situation wasn’t good and pupils had to knock off early,” Kachali said. “I am giving you this example just to show how important power supply is to households, communities and institutions.”

Maureen Zulu, 48, a concerned mother told MakanDay. “Lack of power or energy is making it difficult for our children to pass exams. Surely in this time and age, our children don’t need to go through such.”

This single example is just one manifestation of what economists refer to in dry, abstract terms as Zambia’s debt crisis.

Zambia’s struggles to repay loans to international banks worth billions of dollars have put the country’s finances into a tailspin.

It has seen spending on social services including health and education reduce by 21 per cent between 2019 and 2021, says anti-poverty campaign group, Debt Justice.

To the children, parents and teachers at Nadalitsika, this is the reality of Zambia’s sovereign debt crisis.

And the effects are rippling out to communities nationwide.

Payback time

From 2011, Zambia went on a ten year borrowing spree to fund roads, railway, energy and telecoms.

But cracks started appearing in 2020 when the Patriotic Front government defaulted on a repayment. It sent shockwaves through financial markets.

Today, the country is teetering under the weight of a US$32 billion debt pile.

“Repayments are greater than the country’s contributions to health, education, social protection, water, and sanitation put together,” explained Action Aid country director, Nalucha Ziba.

But President Hakainde Hichilema (pictured, below) insists he has a plan to get Zambia back on track.

Last autumn, his minister of finance and national planning, Dr. Situmbeko Musokotwane told parliament that placing the country’s economy on a firmer footing would not see further reductions to education and health.

Instead, Musokotwane announced that the government will pay down debts by aggressively growing the country’s economy.

At the heart of this New Dawn party strategy is a tripling of copper mining production.

Hichilema’s administration is betting that increased copper production will generate a surge in taxes which can be used not just to repay banks but also kickstart a jobs bonanza.

There is a catch, however. Copper mining relies on plentiful supplies of affordable electricity. Without stable power, the promised economic rebirth may not happen. And in Zambia, power outages are a daily fact of life.

Leading expert Dr Johnstone Chikwanda is sceptical that there is sufficient power to scale up mining production.

The former chairperson of the Energy Regulation and Rural Electrification Boards told MakanDay: “The New Dawn government has set an ambitious target of increasing copper production from the current 800,000 tonnes to 3 million tonnes over a period of 10 years.

“To achieve this target, there is a need to attract more investment in the electricity subsector. At the moment, we do not have adequate electricity capacity to support a copper production increase of more than 300%.”

Mining firms are now beginning to invest in power projects to help increase production. But with the supply of consistent and affordable electricity central to the government’s economic growth strategy, MakanDay Centre for Investigative Journalism and Finance Uncovered decided to look at the country’s state owned power company more closely.

Boxed into a corner

We wanted to examine how Zambia’s sovereign debt crisis has affected one of the country’s most important state owned companies: Zesco, the business that powers the country.

Our investigation, which involved scrutinising corporate financial statements and interviewing experts, suggests that Zesco, like the country it powers, is boxed into a corner.

Owing a range of international banks and power companies billions of dollars in debt and arrears, Zesco’s ability to meet the power needs of Zambia’s population appears to be severely compromised.

It means Hichilema’s recovery plan could be at risk.

Our analysis of the company’s most recent publicly available financial statements showed that:

- Over the past 20 years it has taken out loan facilities worth US$3.6 billion with roughly half from Chinese lenders.

- At the end of 2019, Zesco’s accounts show that it still owed lenders at least ZMW 30 billion (US$1.76bn).

- Outstanding loans to Zesco contribute 5.5% of Zambia’s total debt to overseas banks. They were used for a string of power connection projects and new facilities.

Today inflationary pressures sparked by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are lifting global interest rates.

This could spell further trouble for Zesco. The company’s financial statements in 2019 shows that a significant part of Zesco’s debt is linked to interest rates that are not fixed, but rather go up or down according to general market conditions.

Already onerous, this means its debt burden is likely to edge up even more, piling further pressure on its finances.

Independent power providers

It is not as if Zesco has enough to deal with. Over recent years, erratic rains caused severe water shortages in Zambia. For Zesco, this proved to be an expensive problem.

Hydropower contributes 84% of the country’s energy mix. But with rivers running dry, hydropower generated from Zesco’s facilities reduced sharply. The resulting power cuts hurt businesses big and small.

Amid a clamour for consistent power, Zesco arranged for electricity to be supplied by a small number of privately-owned independent power providers (IPPs).

By 2020, the IPPs contributed “about 20%” of the country’s electricity, according to the government.

But there was a big drawback. IPPs sold power at a price above the level Zesco could sell it on to consumers, which are mostly mining firms.

In 2019, Zesco said it procured electricity at US$0.11 per kwh from IPPs and sold it to consumers at an average of US$0.07 per kwh.

Selling at a loss was one thing. But even worse for Zesco, the IPPs received their payments in US dollars.

This would have been fine if commodity prices were buoyant. During commodity booms, Zambia’s currency tends to strengthen.

But deals with IPPs coincided with a sharp fall in commodity prices on global markets. Suddenly, the years of over-borrowing from international banks caught up with Zambia. The kwacha plunged and those dollar payments to IPPs became far harder for Zesco to afford.

The vicious circle of drought, an inability to sell power at the price it paid to IPPs and the falling kwacha filtered through to Zesco’s financial performance.

In its 2019 accounts, the most recent to have been disclosed, Zesco made a pre-tax loss of ZMW 5.9 billion (US$423million).

A major reason for the loss, the company stated, was down to its rising costs.

And rising costs were “mainly due to the high cost of power from Independent Power Producers”, the company disclosed.

Legal action

The position was so perilous that the Zambian government partly financed payments to IPPs.

But even a government subsidy was not enough. Zesco’s then board chair, Dr Mbita Chitala wrote that in 2019 the company was only paying 45% of total invoices to IPPs.

“The IPP debt continues to accumulate on a monthly basis at over 55% of invoice amounts and thereby threatening our social and relationship capital,” he lamented.

The biggest IPP is Maamba Collieries, controlled by Indian firm, Nava Bharat Ventures. The money it was owed from Zesco was so large it placed Maamba Collieries in difficulties with its own lenders.

To repay them, Zesco took out a US$20 million bridging loan – often an expensive way to borrow money – from an unknown lender.

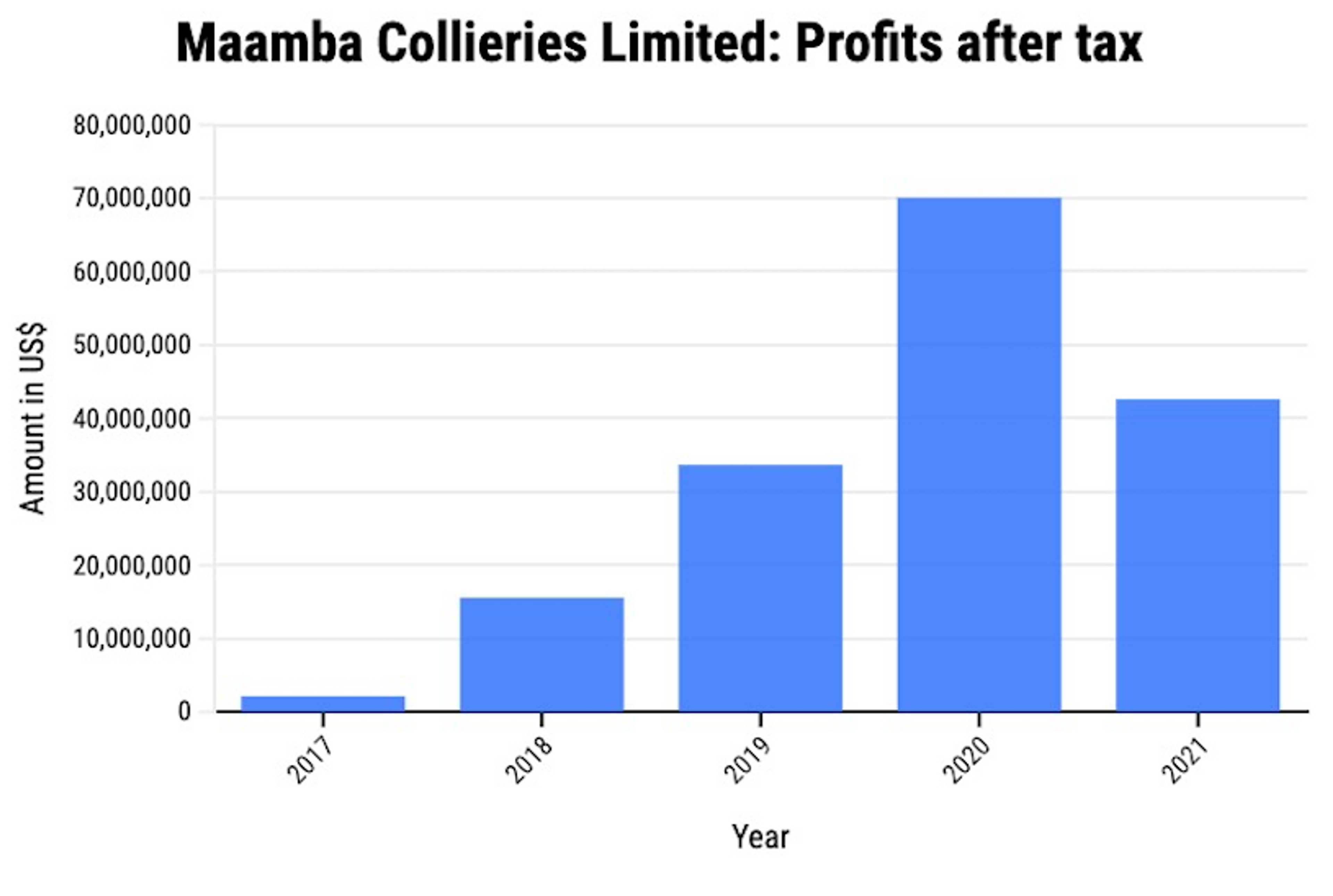

Maamba Collieries was actually deriving huge revenues from Zesco: more than US$600 million in the three years to March 2021. And on paper the IPP was making big profits. In these three years, its accounts showed a very healthy profit after tax of US$146 million.

Maamba Collieries Ltd: Profits after tax, according to its corporate filings. Graphic: Purity Mukami

This sounds good on paper but as Zesco did not pay Maamba Collieries in full for its electricity, arrears of US$432 million piled up.

In October 2020, Maamba Collieries took Zesco to international arbitration in London to recover money it was owed.

MakanDay can reveal that Nava Bharat Ventures has told its investors that the court made a “partial award” to Maamba Collieries of US$250 million, which Zesco was supposed to repay by January this year.

The Ministry of Energy told MakanDay that it “cannot comment on the arbitration matter as it is still in court”.

Maamba Collieries’ parent company, Nava Bharat Ventures, was repeatedly asked to comment for this article but did not respond.

Paper profits

Maamba Collieries is not the only IPP with an arrears problem. GL Africa Energy Ltd is a UK-registered company, ultimately controlled by Kenyan tycoon, Humphrey Kariuki, according to the UK’s Companies House.

A subsidiary of GL Africa Energy runs the Ndola power plant, which currently is not producing power because the Indeni refinery that supplies it with fuel has been shut down.

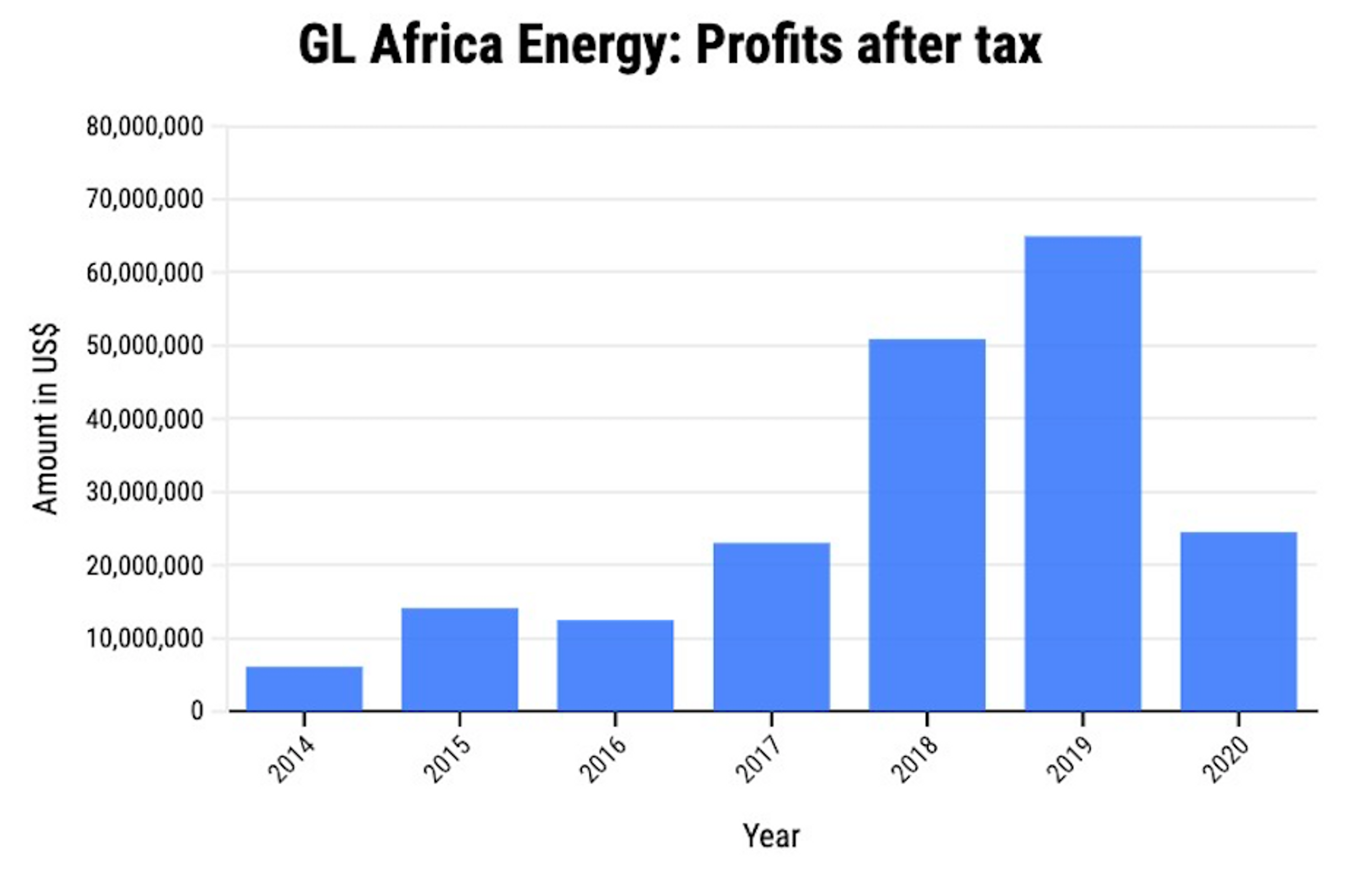

Because GL Africa Energy’s financial accounts are publicly available at the UK corporate registry, Companies House, MakanDay and Finance Uncovered were able to analyse them.

The company has reported massive profits from sales of electricity to Zesco by its subsidiary, Ndola Energy. Its latest accounts to December 31 2020 showed it had accumulated profits after tax of $192 million over the past seven years.

But after digging deeper, it becomes clear that these are currently mere paper profits. The company is in fact owed huge sums – more than $200m – from Zesco, for unpaid bills dating back many years.

GL Africa Energy Ltd: Profits after tax 2014-2020, according to Companies House filings. Graphic: Purity Mukami

While GL Africa Energy’s cash position is strong, a significant amount of its paper profits could be wiped out if Zesco does not pay its arrears to the UK company’s African subsidiary, Ndola Energy.

A source at the Ministry of Finance told MakanDay that the government will assume Zesco’s liabilities to private power suppliers in a bid to promote confidence as it seeks to renegotiate power supply agreements.

The Ministry of Energy told MakanDay in a written statement that it is renegotiating its agreements with Ndola Energy but does not have a timeframe for finishing these negotiations.

The statement added that the government plans to reform Zesco, enabling the state power company to collect more revenue and helping it to “dismantle the debt to Ndola Energy.”

“The ongoing negotiation will allow the parties to develop a payment plan that will facilitate the dismantling of debt,” the Ministry told Makanday. The official statement did not explain what this might mean.

We asked GL Africa Energy a range of questions over a two month period which the company and Schillings, its London law firm, responded to.

GL Africa Energy chose not to make on the record comments for this article.

But in its correspondence, GL Africa Energy stated that the company and its Ndola Electricity Company Limited (NECL) subsidiary are proud to supply the Zambian people with power and help the country reduce its reliance on hydropower.

The company argues that other IPPs charge higher prices than GL Africa Energy and that its US$192 million profit does not paint the full picture.

GL Africa Energy states that NECL has always operated in accordance with all industry-wide legal and regulatory requirements as laid out by the Zambian government, and continues to do so and that the tariffs and profit margins in its power purchase agreement with Zesco are entirely consistent with industry norms and reflective of the regional market risk.

It argues it has to repay US$115 million to its lenders – mostly controlled by its ultimate owner – before it can realise profit.

Whatever happens in the negotiations between Zesco, its power suppliers and its customers, ultimately, the likelihood is that consumers will be forced to pay more for their electricity and the state will be forced to take some responsibility for Zesco’s debt.

Political interference

Experts trace Zesco’s challenges to political interference by successive Zambian governments as well as mismanagement.

Energy expert Dr Johnstone Chikwanda, a former chairperson of the Energy Regulation and Rural Electrification Boards chairperson, like other state power companies in Sub-Saharan Africa, is “technically bankrupt”.

“We have interfered, we have not allowed them (power companies) to operate commercially, we have not allowed them to charge economic tariffs, we have allowed overstaffing to take place there, and we have allowed a lot of inefficiencies in these state-owned companies,” he said.

Kevin Watkins, Visiting Professor at the London School of Economics Firoz Lalji Africa Institute, said: “For all practical purposes, Zesco is a bankrupt company operating in a state bankrupted by the cavalier attitude to debt adopted by previous governments. This is regulatory failure on a grand scale.

“Zambia needs an energy sector that generates the revenues needed to underpin investment and finance access for low-income households, both on grid and through off-grid renewable energy.”

Ensuring affordable, reliable power is key to pushing the new administration’s economic recovery agenda.

It means the Zambian government faces difficult choices. It may be forced to demand consumers and businesses, including mining companies, pay more for power. And it could also try to force IPPs to cut their tariffs.

This threatens to increase the country’s sovereign debt at a time when the government is trying to negotiate with international creditors.

There is an urgency to resolving Zambia’s debt and the finances of one of its most important state-owned enterprises. Ensuring an equitable settlement that satisfies the government, international banks and IPPs is an optimistic hope.

But the next few months will reveal whether the government can secure a deal that does not condemn its citizens to austerity and a life without adequate power.

Resolving it might mean the young pupils at Nadalitsika School no longer having to fetch water from their own homes to see them through classes.

- Additional interviews: Gift Phiri

- This article is part of a series of stories focused on Zambia’s sovereign debt crisis in partnership with MakanDay Centre for Investigative Journalism and supported by Open Society Institute.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.