By Austin Kaluba

In George Orwell’s allegorical masterpiece, Animal Farm, there is a fascinating character named Squealer—a persuasive propagandist with the ability to turn black into white.

Squealer is notorious for distorting the truth, exemplified by his skill in erasing the critical role played by Snowball, Napoleon’s nemesis, during the epic Battle of the Cowshed.

In the course of the battle, Snowball completely outshone Napoleon, who displayed signs of cowardice while the conflict raged on.

So once Snowball has been driven away from the farm by Napoleon’s attack dogs, Squealer sets about systematically erasing his reputation.

No longer is Snowball the hero of the Battle of the Cowshed; now he’s nothing more than a traitor and a criminal. In fact, he is an enemy to the animals’ aspirations and a friend of human beings the animals succeeded in overthrowing.

Squealer drives this point home cleverly by tricking the farm animals testing their memories on the key role Snowball played in the great victory over the hated human oppressor.

But Squealer persuades them that their memories are somehow faulty—that what they think they saw never really happened.

What Squealer’s doing here is constructing an alternative version of history in which Napoleon was the real hero of the hour while Snowball was just a whining coward who ran away from the heat of battle.

The history of Zambian politics, is awash with examples of political heroes who have been sidelined, portrayed as playing second fiddle or pushed to the periphery of not playing any role in the struggle for African advancement and independence.

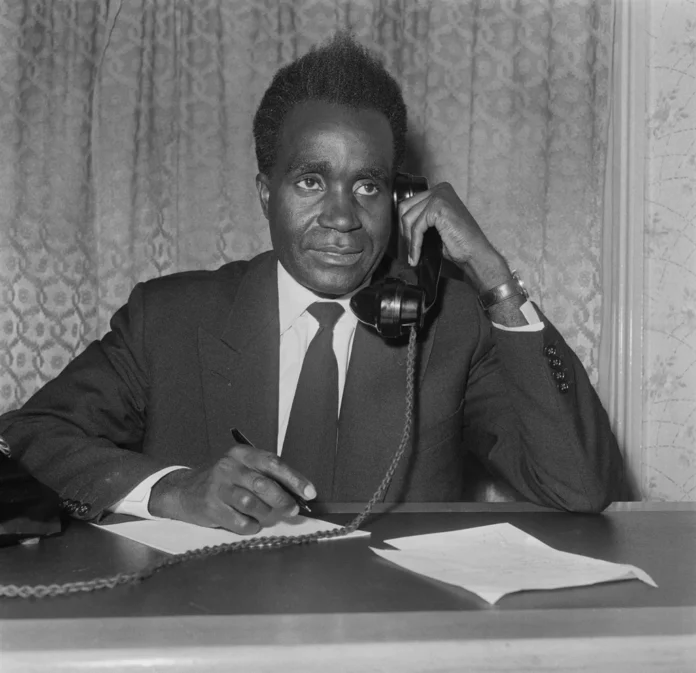

The foremost political hero in this category is the father of Zambian nationalism himself Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula, the leader of the African Nationalist Congress (ANC).

Though now an airport has been named after him, he never received the honour he deserved by UNIP nationalists who worked with him in ANC.

To understand what really happened, a serious student of Zambian political history should rely on reputable scholars like Giacomo Macola, a specialist in the political and military history of central Africa, with a particular focus on Zambia and the DR of Congo in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Macola has acutely challenged the common tendency to explain away the rupture of Zambian nationalist unity in the late 1950s acutely noting that the inevitable consequence of the personal foibles and supposed growing moderation of Nkumbula was not the reason ‘Old Harry’ was shunted almost into oblivion by young UNIP Turks.

This is revelatory because poor scholarly work coupled with word-of-mouth history made many Zambians believe numerous falsehoods and half-truths peddled by UNIP nationalists about the marginalised patriot.

Rejecting this facile narrative, Macola has foregrounded the true complexity of Nkumbula’s nationalism and the contradictoriness of the social interests that it strove, but ultimately failed, to reconcile.

The formation of ZANC/UNIP, Macola argues, had much less to do with Nkumbula’s flaws than with the eruption of hitherto latent socio-economic and ethnic conflicts that pitted the Bemba group with its allies against the Bantu Botatwe grouping.

To quote Macola again, ‘UNIP’s wrath at Nkumbula was more and more frequently converted into a blanket condemnation of his remaining followers – ‘idiots’, ‘simple souls’, ‘Tonga peasant farmers […] whom [he] robs [of] their money to squander on beer and other immoral ways’.

The scholar further notes that these increasingly vitriolic attacks reached their climax with the ‘Catalogue of Nkumbula’s so called political masturbation’, an incendiary pamphlet issued by the divisional headquarters of UNIP in the Southern province at the beginning of 1962.

Macola observes that the text consists of a list of Nkumbula’s alleged financial and political blunders from the mid-1950s. Its vocabulary is both chilling and revealing. Nkumbula was a ‘political rat’, a ‘gangster’, a ‘hopeless and thinkless [sic] roting [sic] politican’ who ‘delayed our freedom’.

However, Nkumbula was not the only victim of the UNIP propaganda machinery, other earlier freedom fighters and champions of African advancement were equally sidelined or undermined.

After the formation of the Zambia African National Congress (ZANC), the young Turks were extremely hostile and pugnacious to the old guards whom they accused of being moderate and colonial puppets.

Early unionists and nationalists who championed African advancement like Godwin Mbikusita Lewanika, Lawrence Katilungu, Dauti Yamba, Dixon Konkola, Paul Kalichini and Paskale Sokota were also sidelined as ba Capricorns or ba Makobo-stooges- by starry eyed UNIP zealots.

One would wonder why Godwin Akashambatwa Mbikusita Lewanika II, who was the Lozi King of the Barotseland from 1968 to 1977 and founded the first political party in the country, the Northern Rhodesia Congress (NRC) in 1948, has not received the recognition a pioneer like him deserves.

His contribution to African advancement is enormous having served as President of the Kitwe African Society of Northern Rhodesia from 1946 to 1948, the Mine African Salaried Staff Association from 1953 to 1964.

It is needless to say he deserves more recognition like having his head on the currency. In South Africa, John Dube, the founding president of the South African Native National Congress, which became the African National Congress in 1923 was abundantly acknowledged by party leaders who came after him.

They never amplified his personal foibles of moderation but recognised the sacrifice he made by challenging white rule at a time when it was riskier than in latter years.

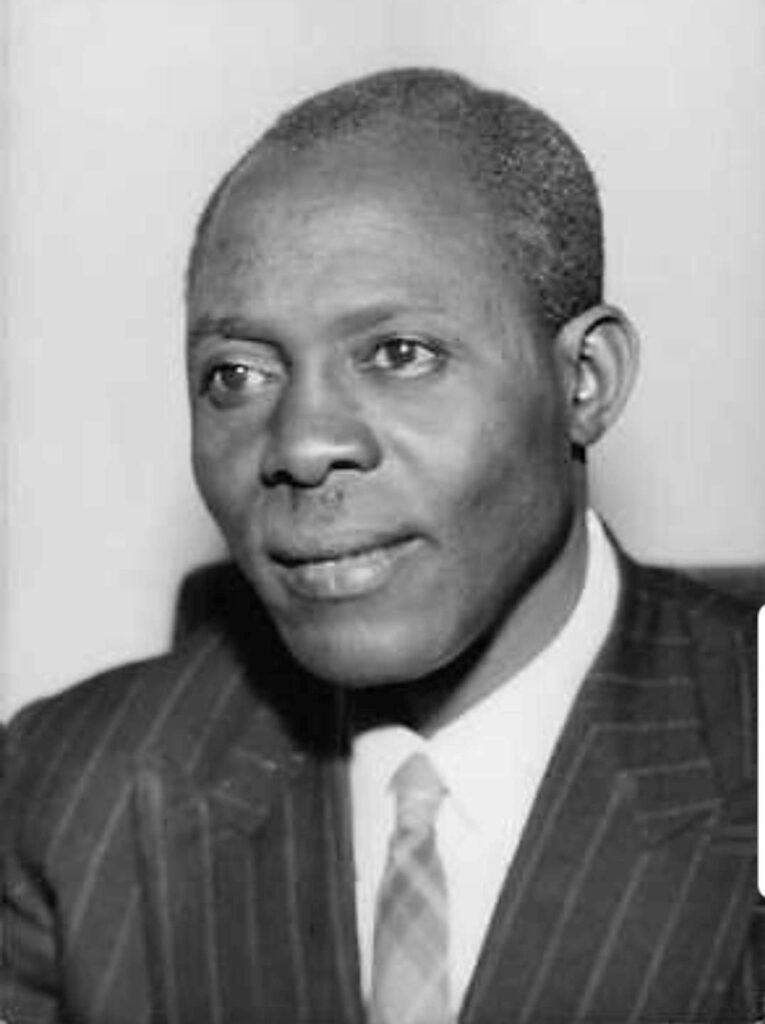

The most powerful black man in Northern Rhodesia in the mid and late 50s, Lawrence Katilungu who could cripple the country’s economy by simply calling a strike of 40,000 unionised members out of 47 African miners was also not respected as an asset to the nationalist cause that the Young Turks somehow hijacked albeit being more focused and radical.

Why was such a powerful man like Katilungu largely unrecognised when Zambia got independence?

Apart from the usual rivalry between the old guards in the struggle for independence and the younger nationalists, the other plausible reason was that he was strongly opposed to the participation of Africans from outside Northern Rhodesia in the country’s politics.

During this period, Nyasas from Malawi mainly Tumbukas and Tongas comprised the bulk of educated Africans who occasionally clashed with local natives especially Bemba nationalists on the political front, the latter who were conscious of their military hegemony and superiority to other tribes.

One needs no guessing which foreign Nyasa and prominent new comer on the political front Katilungu was referring to. It was of course the Lubwa teacher-turned politician, Kenneth Buchizya Mtepa Kaunda, the latter whose charisma and leadership skills were already overshadowing earlier African political agitators.

To justify his hatred for foreign natives, Mr Katilungu called himself ‘Lesa wa bufuba’ (The Jealous God) since he thought he had the right to speak for local natives.

In retaliation, Kaunda and UNIP members accused men like Katilungu to be sell outs. The anti-foreign African stance against Kaunda was shared by other leaders of the time like Dixon Konkola who also used Kaunda’s foreign parentage to disqualify the nationalists from championing the independence cause.

After his death in a road accident at the end of 1961 while serving as acting national president of ANC during most of Nkumbula’s jail term, UNIP nationalists like Munukayumbwa Sipalo deemed Katilungu’s passing as ‘very heartening’.

His legacy as founder of trade unionism in Zambia lives on in Kitwe where Katilungu House, the headquarters of the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) is named after him.

One doesn’t need to guess what could have befallen him if he had lived up to the time Zambia got independence and after.

When UNIP became the voice of the voiceless Africans overshadowing earlier champions of African advancement, men like Konkola, Dauti Yamba, Gabriel Musumbulwa, Alfred Gondwe, Edson Mwamba always bore the brunt of militant UNIP nationalists at party rallies.

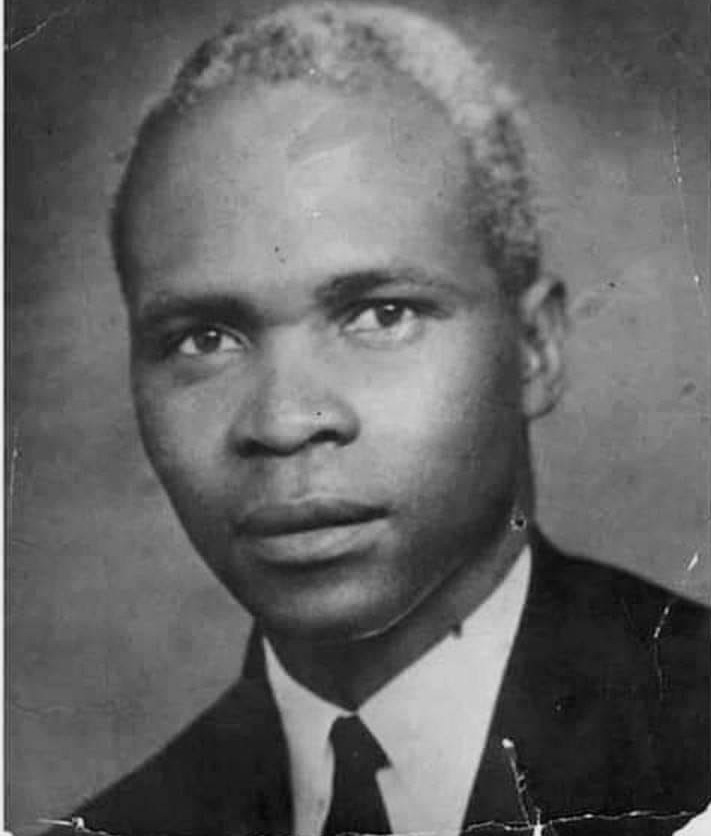

According to Macola, if there were a Zambian History Trivia Contest with the question ‘who was the first president of UNIP? (i.e., the United National Independence Party, which led Zambia to independence in 1964 and ruled the country for the next 27 years), few Zambia would answer ‘Dixon Konkola’.

Macola writes that Konkola’s tenure as the party head lasted only a few weeks; but his relative obscurity seems more a product of the country’s ‘master narrative’, emphasising the ultimate winners (typical, of course, of many national histories).

Some standard texts do not mention Konkola at all, and he is certainly not featured in those which do. Yet in the middle 1950s it would not have been outlandish to have bet on Konkola as the future president.

Other earlier champions of African advancement like the non-combative Yamba were also not recognised by UNIP zealots or incorporated into the party to fight for the common cause of independence.

Part of the mistrust of early political agitators had to do with an organisation called Capricorn African Society (CAS) established in 1949 by Colonel David Stirling who advocated multi-racial alliances with the ‘right kind of blacks’ i.e., those westernised Africans willing to cooperate with liberal Europeans. The movement attracted a considerable following in the mid-50s.

Whatever misgivings UNIP members and other Africans who linked CAS members as vampires or sellouts, it is educated Africans like Donald Siwale and Yamba who laid the ground for nationalism between the years 1941 and 1964 leading to the formation of Federation of African Welfare Societies of Northern Rhodesia which transformed into the first political party.

Yamba waged his fight of championing the underprivileged Africans only to a small extent by addressing meetings in welfare halls, largely in government sponsored forums such as Urban Advisory Council, the African Provincial Council, the African Representative Council, the African Legislative Council, and the Federal Parliament.

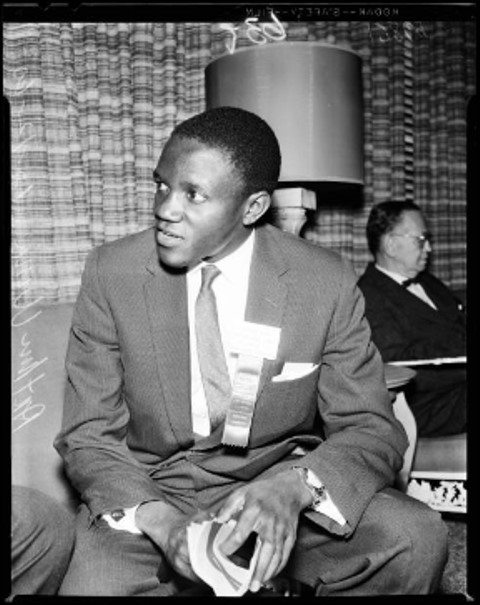

The second UNIP president Paul Kalichini who served as Zambia African National Congress (ZANC)’s deputy president before forming the Africa National Independence Party (ANIP) in May 1959 received very little or no recognition by UNIP especially after the party formed government.

And yet it was Kalichini’s party that merged with the United National Congress Party led by Dixon Konkola, the Freedom Party led by Bary R. Banda to form the United National Independence Party (UNIP), led by Dixon Konkola.

However, Konkola was soon replaced by Paul Kalichini and later when Mainza Chona left ANC (under Nkumbula) to join UNIP, a re-election was called in which Chona was elected the party’s new president.

Chona continued the nonviolence yet militant strategies (strikes, boycotts, demonstrations) of the party and garnered widespread support among the grass root level.

When both Kapwepwe and Kaunda were released from prison elections were called in which Kaunda was elected UNIP president.

In the post-independence Zambia, Kalichini was a forgotten leader living in oblivion in Kabwe, the citadel of nationalism where he had established his name first as a unionist and later as a politician.

The sidelining of founders of movements and political parties continued when Zambia reverted to multi-party politics in 1991 with some names receiving more prominence than others.

The Movement for Multi Party Democracy (MMD) was conceived on 20 July 1990 at a meeting at the Garden Hotel in Lusaka organised by Akashambatwa Mbikusita Lewanika and Derrick Mbita Chitala.

The gathering included various groups, principally representatives of academia and the trade union movement, and individuals who had held posts under the UNIP government. It was registered as a political party in Lusaka in January 1991.

Prior to the repeal of Article 4 of the constitution the MMD operated as a loose alliance of several civil society organisations formed specifically to campaign for the re-introduction of a multiparty system.

Among the organisations and movements, it represented were the labour movement, under the umbrella of the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU); professional associations, notably the Law Association of Zambia (LAZ) and the Press Association of Zambia (PAZA); the Economic Association of Zambia and the University of Zambia Students Union.

Arthur Wina was pivotal in championing for the country to revert to plural politics after 17 years of one-party rule ushered in by the Choma Declaration in 1973.

He was chosen as interim chairman but later lost to Frederick Chiluba at the party’s convention. Chiluba went on to become the second republican president.

It is interesting to note that when the movement quickly morphed into a political party gaining ground and resonating with citizens throughout the country, tribally-inclined members and some citizens started questioning Wina’s credentials.

He suddenly became a Lozi and a drunk! It was clear that many Zambians had issues with his tribe, which for many years after independence had been largely sidelined from mainstream politics and only used for appeasement or to give a semblance of inclusivity.

Later even the role convenors like Akashambatwa and Chitala played in ushering plural politics at the historic Garden Hotel was underplayed in favour of the new comers and hijackers who jumped on the band wagon later.

The history of reform in many countries has seen some reformists being sidelined politically, imprisoned, put under house arrest, forbidden from speaking in public or being put under constant threat and intimidation.

Some authorities have even pushed nearly all of them out of electoral politics by disqualifying them from running for office.

It is up to scholars and objective chroniclers of Zambian history to set the records right since they say “Until the lion tells his side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

Kaluba is a journalist, poet, short story writer, translator and former diplomat

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.