By Reginald Ntomba

As early as the 1980s, the white business community in South Africa foresaw the impending political changes on the horizon. Anticipating the eventual takeover of the government by the African National Congress (ANC), they recognized the need to adapt to the evolving landscape.

At the time, the apartheid regime, oblivious to the shifting tides, staunchly refused to engage with what it labeled as ‘terrorists’—a reference to the ANC.

In 1985, Gavin Relly, an executive with Anglo-American, spearheaded a delegation of white business leaders to Zambia for a meeting with the exiled ANC leadership headed by Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki. Their primary objective was to assess the ANC’s stance on the economy.

This aspect is also explored by Hugh Macmillan in his work, ‘The Lusaka Years: The ANC in Exile in Zambia, 1963 to 1994.’

The business delegation discovered that the ANC, while fervently committed to political freedom, lacked a comprehensive economic plan beyond the ideals of nationalisation outlined in The Freedom Charter—a revered document adopted in 1955, five years before the ANC was banned.

The prospect of nationalisation posed a significant threat to the interests of white business. Upon their return home, these business leaders embarked on a strategic effort to shape economic policies within the ANC to safeguard their own interests.

When the liberation movement was unbanned in 1990 and exiles returned home, white capital went into overdrive, trying to prevent what they imagined was an impending doomsday.

In 1992, Nelson Mandela attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, a gathering of the world’s capitalist elite, where he encountered a strong aversion to the concept of nationalisation. By 1996, just two years into the ANC’s governance, nationalisation had vanished from their rhetoric.

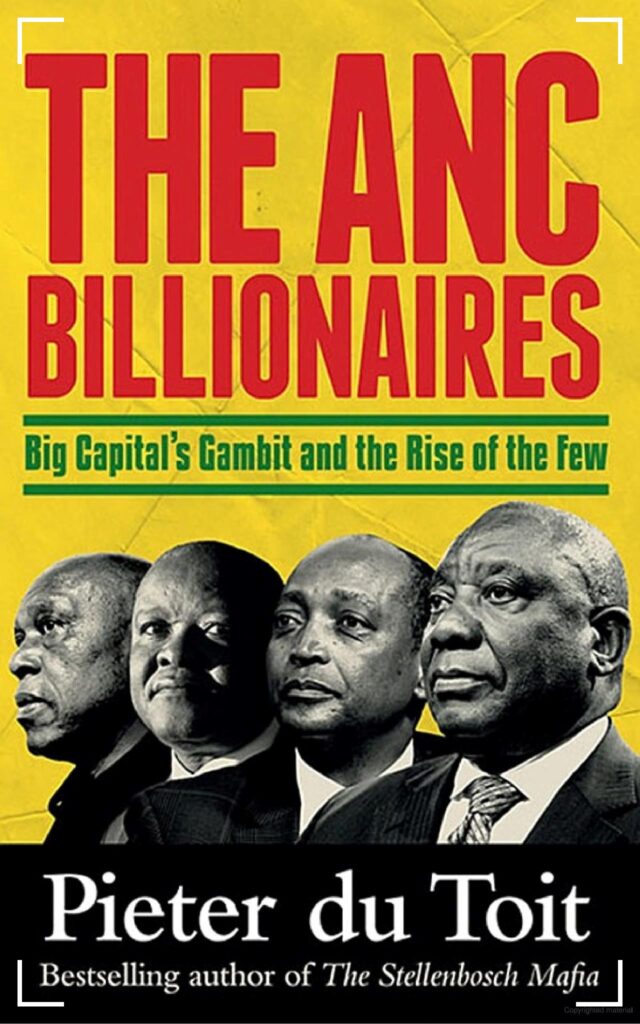

The extent to which white capital influenced this shift, thereby preserving their economic supremacy to the present day, is the central theme of ‘The ANC Billionaires.’ However, it should have more fittingly been titled ‘How the Left Sold Out’ or ‘How White Capital Rigged South Africa’s Economy.’

The handful of politically connected black South Africans who attained billionaire status through the generosity of white capital does little to obscure the stark reality of the country—a profoundly unequal society where blacks are synonymous with poverty and whites with prosperity.

The book’s failure to confront this glaring reality is a significant shortcoming.

The author’s assertion that white business was primarily motivated by a desire to prevent the ANC from steering the country towards socialism is remarkably naive. The real motive of white business was to safeguard their stranglehold on the economy and ensure the exclusion of blacks, relegating them to the periphery.

What better strategy to achieve this than by rewarding the top party leadership with lucrative company directorships, all while feigning support for the eagerly anticipated political transition?

In essence, South Africa’s contemporary economic landscape was meticulously planned and determined within the confines of Anglo boardrooms well before 1994, with the hosts portraying generosity despite their close ties to apartheid.

Considering that these decisions were made in Anglo boardrooms, it’s evident that the turkeys around the table were hardly going to vote for Christmas.

While the ANC may have ostensibly secured political power, white capital continues to exert economic hegemony, leaving the majority of black South Africans worse off today than they were under apartheid. The economic structure was deliberately skewed against them.

It is entirely justifiable for black South Africans to harbour resentment towards their government for failing to deliver on the crucial promise—the economy. Political power that does not translate into economic improvements for the masses is rendered ineffective.

This partly explains why Julius Malema has embarked on a confrontational path, brandishing The Freedom Charter—the same document discarded by the ANC nearly 30 years ago upon assuming power. As the 2024 general election approaches, will white capital thwart his efforts to fulfill his pledges of nationalising mines and banks?

For those seeking insights into South Africa’s political economy in the post-apartheid era, this book serves as a valuable starting point, notwithstanding its contested conclusions.

The writer is a Zambian journalist, author and political scientist

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.