The multilingual musician who wrote songs that transcended social and cultural divides and helped build national unity

By Walima T. Kalusa

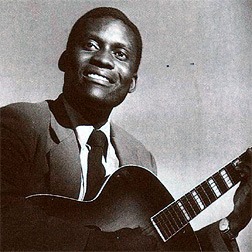

Many people in Zambia today may not have heard of Alick Nkata, let alone know about his enormous contribution to the growth of the country’s music industry. However, Mr Nkhata, whose illustrious musical career spanned the pre- and post-independence era, not only pioneered popular music in the early 1950s, but, up to his demise in the mid-1970s, was the undisputed champion of that genre of music in Zambia, if not in the entire central Africa.

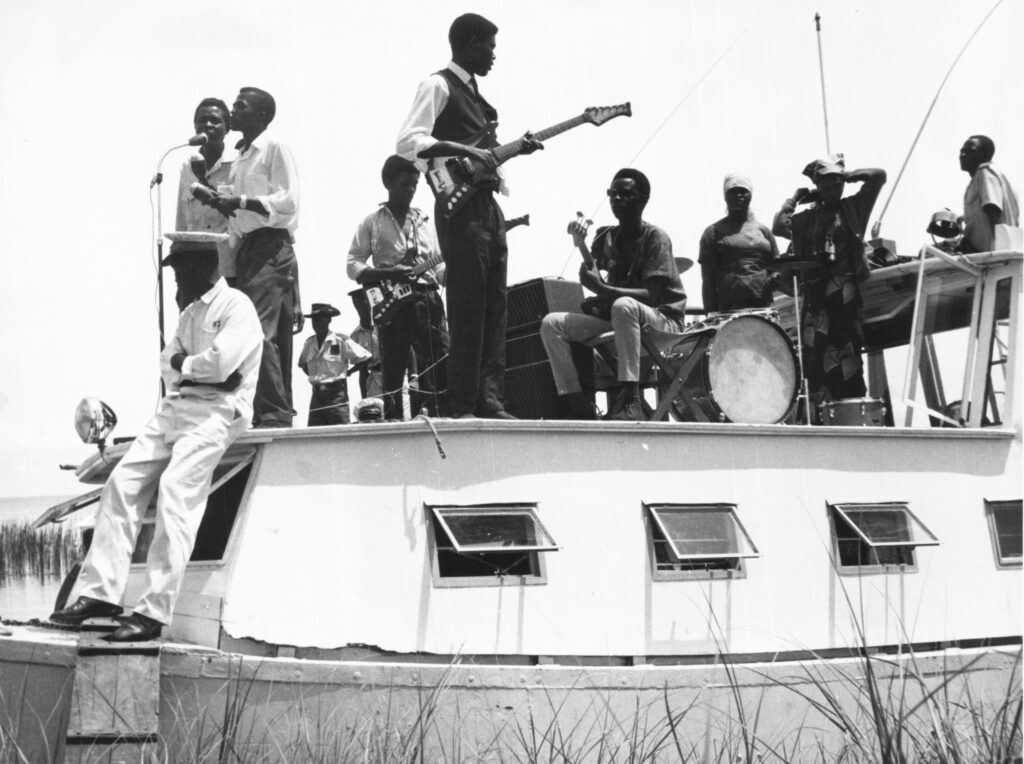

A household name throughout the region in the 1950s and 1960s, he animated the lives of thousands of people who attended his concerts or listened to his songs on radio. Indeed, many people of his generation – including the author’s parents – still have fond memories of the guitarist-singer and continue to sing his songs in times of merry-making. In this sense, his music still lives on today.

Who was Alick Nkhata and what made his music so popular?

Mr Nkhata was born in 1922 in Kasama in the Northern Province of what was then Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). He was an offspring of a cross-ethnic marriage between a Tonga father and a Bemba mother, whose beliefs and culture would later be reflected in her son’s music. Little is known about his early life, save for the fact that the future artist had an abiding passion for music from childhood. After leaving school, he trained as a teacher but, after the outbreak of the Second World War, enlisted in the Kings African Rifles under the East African Division. Like many Zambian men of his generation, he saw action in the Far East, notably in Burma. Unfortunately, there is no documented account of his experiences there.

Mr Nkhata seems to have begun singing and playing an acoustic guitar as a teenager, a hobby that his mother appeared to have keenly nurtured. His singing career, however, really took off after the end of the war when, following demobilisation in 1946, the upcoming artist worked as a field music recording assistant under Hugh Tracy, the famous British ethnomusicologist. Credited with “inventing” the Kalimba, a version of the Imbari, a Shona hand-held musical instrument, Mr Tracy travelled the length and breadth of central and southern Africa with Mr Nkhata recording traditional African music from 1946 to 1949. Mr Tracy, who founded the International Library of African Music in 1954 to record traditional music in central and southern Africa, fervently believed that unless such music was recorded and thus preserved, it could wither away under the pressures of colonialism with its offshoots of westernisation, labour migration, urbanisation and Christianity.

By all accounts, Mr Nkhata came to share Mr Tracy’s belief in the value of preserving authentic African music for the sake of posterity. Together, they toured many parts of colonial Zambia, Malawi and Zimbabwe making high quality field recordings of indigenous songs and documenting local musical instruments. Mr Nkhata’s devotion to preserving African traditional music outlived his work with Mr Tracy. Long after the departure of his British mentor from Northern Rhodesia in 1949, Mr Nkhata continued to record traditional songs for the Central African Broadcasting Service (CABS), which he joined as an announcer-translator in 1950. In 1963, CABS, the forerunner of the present-day Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation, sponsored him to study broadcasting with the Voice of America (VOA) in Washington, US. While there, he became one of the earliest hosts of the African Panorama programme on the VOA English to Africa service. Three years later, Mr Nkhata rose to the rank of director of broadcasting and cultural services at CABS, a position he held up to his retirement in 1974.

Our protagonist did not only record other musicians’ music. He himself was also an accomplished solo guitarist who composed, sang and recorded his own songs. To promote his singing career, he joined hands in the 1950s with Shadrack Soko and Dick Sapseid, an accomplished musician and British broadcaster at CABS, and together they formed the Lusaka Radio Band, which they later rechristened as the Big Gold Six Band. The band’s songs were played regularly on radio. Mr Nkhata continued to churn out music even after CABS’s offices were relocated to colonial Harare in modern Zimbabwe during the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After moving to Harare, he teamed up with leading local musicians there such as Elias Banda, regularly touring and performing music across the country during his free time.

At the height of his singing career in the 1950s and 1960s, Mr Nkhata composed and recorded numerous songs. His most popular hits included Shalapo (Goodbye), Ifilamba (Tears), Tax driver, Icupo (Marriage), Nalikwebele Sonka (I Warned You, Sonka), Balelila Pendeka (Crying for Pendeka), Abalumendo bamo (Some Gentlemen) and Uluse lwalil eNkwale (Kindness Killed the Partridge), all of which he sang in ChiBemba. He also sang songs in Nyanja, Lunda, Chewa, Kaonde, Tumbuka and Nsengaand in Swaka. Mr Nkhata’s ability to sing in so many different languages aptly attested to the versatility of the born-musician and to his conviction that music transcended linguist barriers.

by Alick Nkhata, himself a well know and popular radio personality

As the titles of his hits suggest, his songs, a number of which he composed and sang on the spur of the moment, were avivid commentary on a wide variety of social issues in 1950s and 1960s Northern Rhodesia. As an American anthropologist who met him in the 1950s observed, Mr Nkhata sang of rural and urban life, of sex, of love and of loneliness, and so on. In Abalumendo bamo, for example, the “Dreamer of Songs,” as Nkhata called himself, warned young men against wasting money on Bakapenta – that is prostitutes who painted their lips. In another popular hit, he sang of awkward, ignorant wives from rural areas who brought shame upon their urban husbands by cooking tea leaves as if they were vegetables.

But Mr Nkhata often also sang of more serious issues. In 1966, for instance, he composed a song in praise of Zambia’s First National Development Plan that sought to improve state management of the economy, education and cultural development. Similarly, before his death in the 1970s, he composed a song in which he challenged the international community to remove from power the illegal white minority regime of Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). Whether satirical, sentimental or melancholic, Mr Nkhata’s songs no less entertained than educated his fans. Eyewitnesses recall that people who attended his concerts would be laughing one moment and crying the next, depending on the nature of the songs the talented musician played.

By the time he retired to his farm in Mkushi in 1974, Mr Nkhata had recorded thousands of songs that included his and other musicians’ music. Through his own art, he championed peaceful coexistence, for his music transcended barriers of ethnicity, racism and other related “isms” that sow seeds of social discord in society. Indeed, some of his songs in the 1950s ridiculed the exploitation of Africans, colour bar and racial discrimination, but they were never recorded due to the political temperature of the day. Even in retirement, Mr Nkhata continued composing and singing at his farm. He eventually became a member of the Performing Rights Society, an umbrella body of artists based in the UK from which his family continues to derive royalties for his music.

Mr Nkhata was killed at his farm by Ian Smith’s forces from Southern Rhodesia in 1978 during a raid against a nearby camp of nationalist fighters under the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU). His demise, however, failed to extinguish his music, which continues to be played on radio programmes at ZNBC, where his recordings are localised. His music also lives on through the efforts of his son, David, who inherited his father’s love for composing, singing and recording songs. David Nkhata, who continues to live on his late father’s farm in Mkushi and who vehemently opposes computerised music, is poised to release a new album before the end of 2012, thus carrying on the family tradition of singing and entertaining people.

Although no serious study has been carried out on Mr Nkhata, he is certainly a towering figure in the history of Zambian music and that of the country as a whole. Through his unequalled efforts to record his own and other musicians’ art, he preserved and bequeathed thousands of songs to the nation and to posterity. His songs, transcending social and cultural divides, further cultivated a sense of national unity, social cohesion and identity.

In this sense, Mr Nkhata’s art became a potent symbol of nation-building both before and after his tragic end. His music possessed teachings that are as relevant to contemporary Zambian society as they were to previous generations. It is no wonder that it still attracts the attention of many Zambians today irrespective of their linguistic, ethnic and historical backgrounds. Through music, the composer, teacher, entertainer and social critic educated multitudes of people, drawing their attention to social issues, and, after independence, pressing political problems. His art also broke ethnic and other barriers and was an important element in nation-building after independence. For all these reasons, his name deserves to be etched in Zambia’s hall of fame.

This story was first published in the October 2012 edition of the Bulletin and Record magazine.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.