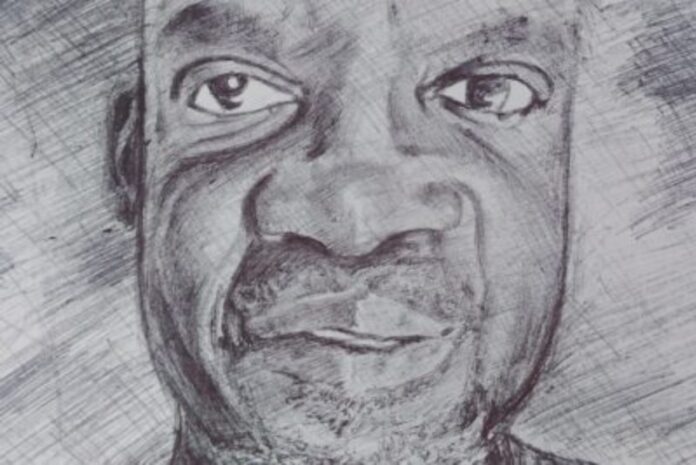

By John Mukela

EXCLUSIVE for MakanDay

Part V

IN the last of his final installment of this exclusive series, JOHN MUKELA, MakanDay’s managing partner, recounts his ordeal with Covid-19

We had come into the ward as complete strangers but as the days wore on, we formed an invisible bond. Even Wuhan seemed to become one of us, despite the English-Chinese communication barrier.

It was only with the aid of his mobile phone’s Chinese-English language translator app, that Wuhan was able to string together a couple of English words. Most times, he would talk into the phone’s microphone in Chinese, and a woman’s automated voice in the phone would bark out Wuhan’s audio in English. The listener would then talk back into the phone, and the app would shoot back in Chinese. And so back and forth, the conversation would continue.

It seemed such a long time since I had first seen Wuhan that afternoon, standing anxiously and nervously in the UTH casualty ward with his bags of luggage.

Like Donald Trump might have been, my loathing for Wuhan was driven by my perception that he was the human epitome of the virus itself.

That is why early one morning before dawn, in the dim light filtering from the main corridor, I caught sight of Wuhan sitting on his bed and I was shocked at what I saw.

Yes.

There was someone on Wuhan’s bed and it wasn’t Wuhan.

What I saw that morning was a man in pain, suffering, a man caught up in the agony of a dreadful killer disease.

I felt his pain, his suffering, because I knew what it was and I had suffered the same.

Wuhan seemed transformed and instead of seeing him through my Trump induced bigotry and prejudices, I saw instead a Covid-19 patient – battling with a killer disease.

I saw a child of God, struggling for survival, just like all the rest of us.

The shock was too much and I turned away.

The nurses did their rounds early in the morning around 04hrs and again in the evening around 20hrs. Once in a while, the resident doctor on duty would accompany them. The first part of the round would be to take vital readings such as body temperature, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, etc.

Next, they followed up with their goodies of syringes, pills and vials of antibiotics and other injectables.

Among several, my regimen consisted of Azithromycin, Dexamethasone, Ceftriaxone, vitamin C and paracetamol.

During one of these visits, the doctor on duty said to me, “tell me, do you go to church?”

The question caught me off guard.

As a young pupil at Livingstone Convent Primary School, our head teacher was a short and stern Irish nun called Sister Anne Plunkett. Another I remembered was the jolly kind faced Sister Irene, and an attractive young lady teacher called Miss. Brown.

The head of the parish was a tall athletic priest, Father Jude McKenna. Under his loose grey frock, you detected his muscular frame as he darted across the school grounds, a spring in his step. Not only was he responsible for serving mass on most days, and especially on Sundays, but he was also a trained black belt judo expert and instructor. As Father Jude’s chief altar boy, I was privileged for the honour.

One Sunday, I decided to miss mass. The problem was, it wasn’t just an ordinary Sunday.

It was Easter Sunday.

Too ashamed and guilty at what I had done, I was too shy to ask Father Jude’s forgiveness. For letting the parish down and especially, for letting him down and so, I stopped attending mass altogether.

I wonder to this day, why I decided not to turn up that Sunday.

Was it stage fright?

Induced by the big occasion of Easter Sunday?

As I grew older and turned into a young man, my Church attendances became even more sporadic, reduced mainly to weddings, funerals, and the occasional guilt-ridden trip.

The doctor was waiting for my response to his question. Did I go to church?

“Yes,” I lied. “I do.”

“And what church is that?” he asked.

“Roman Catholic.”

“Oh! I see!” I saw him jot something down in the file in his hands.

Although we were reasonably taken cared of by the medics, it was also clear that there were not enough nurses to attend to patients.

Also apparent was that many of the nurses I had encountered earlier on at UTH were ill equipped and lacked appropriate knowledge and training to deal with a virulent epidemic such as Covid-19.

I had also gathered through my interactions, that the nursing staff at Levy Hospital were forced to camp for at least three months on site without breaking to go home. They slept at nursing quarters at the hospital and after three months, they would rotate with another crew.

The nurses were petrified and fearful because of the seriousness of the disease and the general situation.

The doctors were equally over-stretched, and it was very difficult to see a doctor, especially with the spike in cases at the end of July.

The chief doctor at Levy had himself been hospitalized after testing positive for Covid-19. It showed that the disease had no boundaries and didn’t choose.

I heard that the doctor who had been on duty before our arrival at Levy was a very responsive doctor, and that he would interact with patients, telling them how they were doing and how they were reacting to the medication.

His chats went a long way to reassure patients. But after the spike of new admissions at Levy, Dr. Mbewe suddenly disappeared. In his place, a young doctor was assigned. But he was so inexperienced it was possible to see he was even afraid of the questions from patients.

One Sunday, he had expressed the likelihood that two of the patients in my ward who appeared to have significantly recovered would be discharged by the next day Monday.

But by lunchtime, neither Dr. Lungu (not his real name) nor any other doctor for that matter, had turned up. The two patients were feeling despondent, having looked forward to their discharge.

So where were the doctors then?

Our suspicion was that they had been commandeered upstairs to the VIP wing attending to infected members of parliament and politicians.

By default, Covid-19 had somewhat levelled the medical playing field in Zambia. The border lockdown meant no more business as usual. It meant bye bye Morningside Clinic in Jo’burg for Cabinet Ministers for their medical needs. The lockdown meant if you were not admitted right here in Lusaka, whether or not you were a hot-shot politician, you risked death.

As the days wore on, it was inevitable that we would become familiar with each other and begin to share our personal struggles with Covid-19 – patients and medical staff alike. We were all in this together.

One day, a nurse disclosed that before his transfer to Levy Hospital, he had been stationed at the UTH Covid Isolation Centre. I mentioned that my experience of the Centre had been most unpleasant, and that as far as I was concerned it was a death trap. My colleague patient, Zambia Air Force (ZAF) Warrant Officer Mulenga, who was a driver with the ZAF, also concurred.

I said during the time I had been admitted at the Isolation Centre not once did a doctor come to see me. All I had seen were cleaners, the occasional nurse, and no doctor.

The Levy nurse said the difficulty at the Isolation Centre was that patients were “suspect Covid positive,” and that therefore before confirmation of their Covid status, there was nothing much that could be done for them. This was why doctors didn’t see the need to attend to them.

I countered that despite the lack of confirmatory evidence of patients’ Covid status, probably 80-90 per cent of Isolation Centre patients could reasonably be said to be Covid positive. So why not accord them the necessary medical care?

Instead, many were left isolated in their single rooms, often dangerously ill, with little medical support from staff, especially at night.

The nurse confirmed that there was “a lot of stigma” concerning suspect Covid patients even from nursing staff themselves. This admission partly explained staff’s reluctance to attend to patients.

My mind wondered backwards to an earlier phase in my illness.

I was back at my first port of call – the UTH casualty ward, and I had noticed something strange. Using a pin, someone had stuck a soiled dirty handkerchief into the mattress of my hospital bed and I was seeing the hankie for the first time.

How long had it been there? Who had stuck it into the mattress next to my pillow and why?

Was it from a Covid-19 infected patient?

Was it a ploy to transmit whatever vermin lurked in its folds onto the patient lying on that bed (me?) or was it merely a simple coincidence?

Many days had passed since that shocking discovery of the filthy hankie and having since been transferred to Levy Hospital, I had reason to believe that now I was well and truly on the road to recovery.

With the blue theme colour of the Levy wards, next to each trolley bed with its single mattress still wrapped in factory plastic covers, was a blue bedside cabinet with multiple cupboards and a small shelf. Ceiling to floor curtains suspended by a ceiling railing separated each bed.

Each bed was equipped with medical emergency paraphernalia such as a negative force suction hose connector, an oxygen flow water pump and emergency intercom for communicating with nursing staff at the central nurse station desk in the main corridor.

There was a reading light at the instrument console next to each patients’ bed and a couple of electricity plugs. At night, when I felt energetic, I sat up in my bed and wrote notes in my notebook detailing some of my experiences. In the centre of the two double ward windows was a sturdy single hand washing basin with hand-washing gel. The walls of the ward were blue grey. Metre square cream tiles with grey trimming made up the ward floor.

In the men’s shower room, the two toilet cubicles were clean and well equipped with the necessary supplies for patients’ use. Two showers with constant and piping hot water from two hot water geysers supplied water for patients’ use.

Meals were adequately provided, consisting of freshly cooked Zambian dishes for lunch and dinner and bottled mineral water. Breakfast was usually a boiled egg, a choice of either brown or white sliced bread, margarine or peanut butter, powdered milk and sugar, a tea bag, and hot water. By Zambian standards, it was a good place to fall sick with Covid-19, and unless a patient was seriously compromised with other underlying issues, the chances of recovery were equally good.

Slowly, my appetite began to return and I was eating as much as I could manage.

The coughing began to ease and my lethargy began to wane. I was getting back to humanity.

Whenever I felt the urge and the strength, I took walks to the edge of the corridor and watched the world go by through the open gaps in the wall. Unless something drastic was to occur, I finally realized that I would eventually be returning home.

Getting more acquainted with each other in the ward, we told stories. The resident patient we had found upon our arrival, Warrant Officer Mulenga, recounted how a certain General had the bad habit of setting up the sentries on duty at his official residence. Often while on duty, the sentries would notice that at daybreak one of them would discover that his assault firearm was missing. As every soldier knows, in the military, the last thing you want is to loose your firearm. It is a very serious offence, for which a soldier will be court marshaled. As a soldier, your weapon is more than your wife or husband who can never leave your side.

One night one of the sentries at the General’s residence noticed a figure crawling in the dark and immediately alerted his colleagues. The sentries immediately opened fire, missing the crawling figure by a whisker. Later, they realized it was the General himself, and he was in the habit of stealing the sentries’ firearms “in order to test their vigilance.”

He was extremely lucky to be alive.

In another story, another wayward ZAF General named Mulenga, had made it a big issue of instructing his sentries that after midnight, they should always expect that he would be indoors at home and under no circumstances were they to entertain any suspicious movements in the yard.

One night, his wife called saying she had just arrived from some family trip out of town and requested her husband to drive and pick her up from the station.

It was well past midnight, but the sentries noticed one of the General’s official ZAF vehicles rolling slowly and suspiciously towards the gates with all its headlights switched off.

With no questions asked, the sentries immediately opened fire, killing the General instantly. They thought it was an intruder and were simply following the orders they had been given by the General himself.

Of the four of us in the ward, Wuhan was the first to be discharged one Saturday morning. We all could see that he was impatient to leave and ecstatic that he was going home. Before his departure, he distributed most of his remaining food, packets of Chinese noodles, fruits, etc. We all exchanged contact details with him and implored him to remain in touch after his discharge. It was then that I discovered his name, which together with his mobile telephone number, he wrote down in my notebook in his firm upright handwriting in both Roman and Chinese characters.

His name was Chendog Feng, Next to leave, several days later, was our ZAF story-teller, Warrant Officer Mulenga.

After Mulenga, next to be discharged was “silent patient” Lasford Shamilimo.

Before his departure, I made it a point to get his perspective of his experience. Despite our chat not lasting very long, little did I know how much I had exerted myself. Lasford was elated. He was going home after about three weeks in isolation with Covid-19 strangers.

After my chat with Lasford, I ambled over to my bed and was immediately seized by a long spasm of violent coughing, wheezing and gasping for air. I was still far from well. Hospital staff brought our lunch. By dinner time I still hadn’t touched it. All afternoon I lay huddled in bed. Lasford’s departure had affected me in more ways than I might initially have realized. I was depressed that of the four original crew of patients, I was now the only one left and all my colleagues were gone. It was true that you do bond together. Now the last of that bond was gone.

Days passed. Other patients joined me in the ward. Some were discharged. Others replaced them, and they too were discharged. Little by little I gained strength and gradually, hope. I sensed that just like them, my day was also fast approaching.

During one of his ward rounds one day, I ventured to ask the doctor a question that had been troubling me for some time. By then, we were all on easy speaking terms, with the nurses, with the doctors, with our fellow patients.

“Tell me doc,” I said, “that day, why did you ask me whether I go to church?

Dr. Sikanyika lowered his face and glanced at me through his horn-rimmed spectacles.

“Oh!…That day!…it’s because we need to know.”

He paused.

“In case the patient doesn’t make it. Last rites. You see, some patients are non-believers!”

Several days later, one morning without much warning, a nurse approached my bed and uttered the magic words.

“Mr. Mukela,” she said in a cheery voice, “you can start getting ready. You’re being discharged!”

My last rites would have to wait. I had made it.

My son Liswaniso was waiting in the hospital car park.

Outside, the sun was shining softly.

Walking to the waiting car felt strange. I smelt the sweet scent of the late afternoon breeze and inhaled deeply. It felt like I had just disembarked from a very long tiring flight, from a very mysterious and strange distant land, and I was about to proceed through passport control heading home.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.