By Golden Matonga, Mercy Chegunda, Earlene Chimoyo

Ethel Moyo, born and raised in Lilongwe Mtsiriza peri- urban township, claims she was forced into a marriage with a Chinese man.

As the price of brides becomes increasingly unaffordable in China, Chinese men are looking for cheaper options in other countries. This seems to be creating a disturbing market in poor countries like Malawi as they work through ruthless agents to buy women to marry.

Some of the arranged marriages border on human trafficking with parents falling for the high prices that agents offer for their daughters.

For some young women, it is a way to escape poverty. However, many brides that the Platform for Investigative Journalism (PIJ) spoke to say they were forced into marriage by manipulative agents who bribe their parents. Some not only claim to have been underage when these marriages were arranged, but also they are subjected to physical and emotional abuse by their Chinese husbands – and in some cases still by the agents who arranged the marriages.

The PIJ findings come amidst growing concerns of human trafficking, with Malawian women being trapped in various countries, including Oman, Kuwait, Iraq and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The crisis unfolds against a backdrop of economic hardship in Malawi, where job opportunities are scarce, largely due to an overreliance on the failing tobacco industry.

Hobbled by inertia and corruption, Malawian law enforcement agencies appear ill-equipped to tackle this problem.

Agents, some of whom still maintain close ties with the targeted families, have gained significant influence and power in this trade. When confronted with evidence of their involvement, they have responded with threats and intimidation. The PIJ can identify Austin Banda as one of them.

Ethel Moyo is one bride who the PIJ spoke to. Her story epitomizes the plight of many. She was coerced into marrying Zhang He, a Chinese street artist and watermelon vendor. Ethel was not the intended bride, her sister Beatrice was. However, her sister got cold feet and managed to escape. Ethel’s mother then offered Ethel as a replacement and forced her to comply after agents threatened her. Although Ethel was only 17 years old at the time, her mother lied, saying she was 25 so she was of an eligible age.

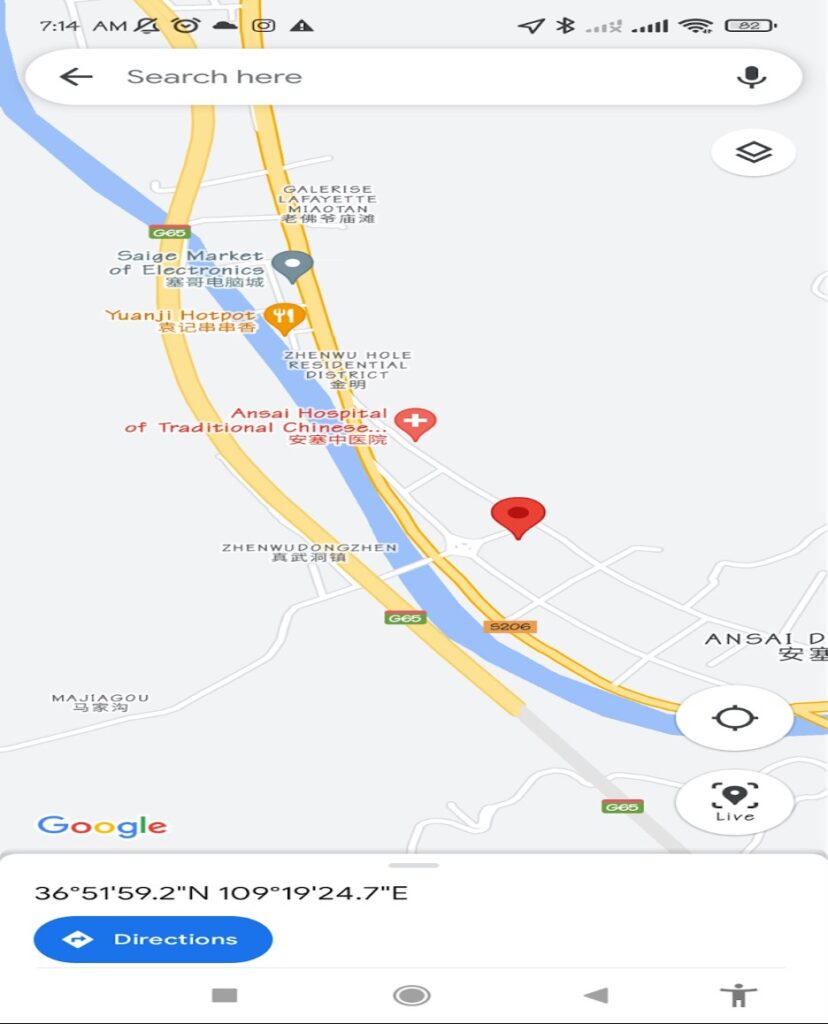

Over a bad phone connection via WhatsApp, Ethel, who was born in 2005 in Lilongwe, explained how she ended up with her husband, who trades in Yan’an City in Shaanxi province, China.

While the marriage brokers allegedly paid about K400 000 (about R7 000) to her mother to secure Beatrice, they paid much more to the people who facilitated the deal. However, while waiting to be flown to China, Beatrice ran away from the pre-departure camp in Lilongwe’s Chinsapo Township. When the agents put pressure on Ethel’s mother, who runs a low-end restaurant in Mtsiriza township in Lilongwe, Ethel was forced to replace her sister.

“My sister was chatting with one of my mother’s friends. She asked my sister if she would go to China to get married. She was promised a rich husband,” recalled Ethel, a primary school dropout.

Her sister had just married her boyfriend in Malawi. However, a family friend and a businesswoman identified only as Eliza, who also lives in Mtsiriza and seems to arrange marriages between Malawian women and Chinese men, suggested to Beatrice that she elope with a man who was on a trip from China to find a wife.

“The Chinese guy came to Malawi and was sleeping at a lodge. The people were working behind the scenes arranging the marriage with the Chinese guy. I just heard one day my mother telling me that they were going to drop her (Beatrice) off to a Chinese person. After a few days, my sister, while staying with the Chinese person in Chinsapo, started saying she was having a bad feeling about the arrangement and even had nightmares about it. So she escaped from the marriage in Chinsapo … around March,” said Ethel.

Ethel describes how she was put under significant pressure and threatened by Eliza, another facilitator called Bhoko and Banda to replace her sister, especially as the family had been paid. The agents reportedly threatened her mother with arrest as she had agreed to the deal and took the money.

Ethel eventually agreed to go. The facilitators, a driver and Eliza, whom Ethel calls “Auntie Eliza” but is allegedly related to Banda, took Ethel to Manolo Lodge in Chinsapo. There, they kept her for a month before flying her to China.

“The Chinese reportedly gave the facilitator K500 000, but she gave my mum K400 000. My sister was not given any money. She was given a phone, but it was taken away from her. I was told to be telling people I am going to China for school,” said Ethel who also describes how her mother had used the money from the agents to buy things such as food, cooking oil, a bag of maize flour, soap, washing soap, biscuits, and margarine.

Banda took Ethel to the immigration department to apply for a passport and allegedly told her to say she was 25 when she was in fact 17. He reportedly threatened to beat her if she told the immigration office her actual date of birth, which the agents changed to 1998.

“Austin and his brother are in this business. They both facilitate the trade,” claimed Ethel, specifically accusing Banda of threatening her to obey their orders, including once ordering her to hug the husband in a show of public affection.

Ethel and Zhang officially married in China at the state certification office. That was when her life became a nightmare, she said.

She described her marriage to Zhang (33) as loveless and said she struggles to make love to her husband, whom she “detested” from the word go. Zhang’s response has been anger, often manifesting in violent and verbal attacks. It is also a marriage born with a major handicap: a language barrier. He does not speak her native Chichewa or second language, English, and Ethel does not speak Chinese. They use their phones as a translator.

“He beats me up with a belt when I refuse sex,” said Ethel, adding she has not told her mother about the abuse.

Banda still plays a role in her personal life, reminding her to continue to bear the suffering for the sake of the arrangement, and continually warning her that no money will be forthcoming for a return.

“Austin even calls me while here in China to threaten me,” she said, “He says he can’t give me transport to get home. He calls to check if I am having sex with the husband. He even questions why I am not getting pregnant. He asks me, ‘Are you taking anti-pregnancy pills or aborting?’ He says he hears I am not having sex with the money. I have been complaining that my husband beats me, but Austin says, “ banja ndi kupilira – you need to persevere.”

Ethel, desperate to escape China and her unhappy marriage, contacted a Lilongwe-based lawyer, Stanley Chirwa, who has been working with the authorities, including the Chinese embassy, which has brought Interpol into the loop and wants to bust the syndicate trading Malawian girls into China.

Souring bride prices in China

Zhang’s income from playing as an artist and selling watermelons is not enough to buy a bride in China, but it is in Malawi.

“Here, women are so expensive,” said Ethel, who lives with her husband and his father and mother in a compound.

According to the New York Times, local bride prices are skyrocketing across China, “averaging $20 000 (about R385 000) in some provinces — making marriage increasingly unaffordable”. The payments, the newspaper said in a recent report, are typically paid by the groom’s parents, and poorer men in rural areas must pay more to marry because the women’s families want a better guarantee that they can provide for their daughters, a move that instead can plunge them deeper into poverty.

“This has broken many families,” Yuying Tong, a sociology professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told the NYT. “The parents spend all their money and go bankrupt to find a wife for their son.” Cue a cheaper option, Malawi. A country where the majority live on less than a dollar a day, where extreme poverty is the lived experience of millions. According to Ethel, Zhang got the idea of a Malawian bride from a friend who married a Malawian woman called Spiwe. According to Ethel, Spiwe was 20 when she married. Ethel also knows another girl, Joyce, from Malawi’s second-largest city, Blantyre, who is also married to a Chinese man.

“Out of the women married off here, I am the youngest and being abused,” she added.

The women, on the other hand, are being driven out of Malawi due to economic challenges, including growing inequality and lack of jobs, Betcheni Tcheleni, a Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences economist, said. “People think if they go out of the country things will be better, maybe they will find a job, maybe start a business. People try to go to unimaginable places just to ensure they can fend for themselves.”

He said human trafficking and economic migration are likely to continue until the country addresses the fundamental economic challenges that will ensure job creation.

In May this year, police at the Kamuzu International Airport (KIA) in Lilongwe arrested three Chinese nationals, two men and a woman, over attempted human trafficking. The men, Zyang Yan Qing and Zhon Yanhu, and a woman only identified as Miss Chen, were about to fly out of the country with two Malawian women.

They had been married to Chinese partners, according to the UN agency fighting drugs and crimes, UNODC. “The case includes obtaining a marriage certificate through fraudulent activity,” UNODC national director Maxwell Matewere said in an interview.

A spokesperson at National Police Headquarters in Lilongwe could not provide an update on the case and did not respond to the findings of the PIJ investigations.

The UN office, though, has also registered other cases involving a man trying to forge marriage certificates.

“I am also aware of some gentleman who contacted a certain lawyer in Lilongwe looking for the possibility of legal support to register an organization in Malawi whose agenda was going to be recruitment and arrange a marriage for women in Malawi,” Matewere added.

The PIJ found out about more women married to Chinese men during the course of the investigation, and nine of their social media accounts had one familiar mutual friend, Austin Banda.

Banda threatened a PIJ journalist when approached for comment. He vehemently denied being an agent or knowing Ethel. He also claimed he was not involved in her marriage.

Unlike the UN agency, the Malawian government claims to be oblivious to the trend. The ministry of gender, through a spokesperson, said it was unaware of it. The ministry, though, became defensive over reports that minors are among those involved in the industry, brushing aside aspersions that any of its officers would be involved in the certification of marriages that involved anything untoward.

“As a ministry, we are not aware,” spokesperson Pauline Kaude said in a written response.

“The government has a Trafficking in Persons Act in place and the policyholder is the ministry of homeland security. It has trained protection officers, MRA officers, and police officers. It has also done sensitization of the chiefs and community members at large in all districts and villages around the border posts to check children that are going out and coming into the country to see if they are accompanied by an older person and have valid travel documents which are subject to verification,” Kaude added.

In an interview, Ethel’s mum rejected her daughter’s assertions that she was in a forced marriage. She also denied ever being paid to give her hand in marriage.

“My daughter went to China for reasons. Her cousin is in China and invited Ethel to work for her either in a shop or to take care of her children. I heard there are agents looking for women to marry, but I couldn’t allow her to go if she was going there for marriage. Her cousin is married there, and the husband has shops.”

As far as she knows, her daughter is happy. She said Ethel’s cousin is married to a Chinese man, but insisted she did not know if Ethel was married. She also denied knowing about “Auntie Eliza”.

Indeed, some brides appear to be happy or comfortable with their arrangement – at least, based on their social media postings. Some post pictures of their wedding days, clad in white wedding dresses, some in Valentine’s Day attire, looking exotic and smiling. One bride has a picture of herself and her husband as a Facebook profile picture, the couple looking relaxed and smiling. However, the majority were unwilling to be interviewed for this investigation.

That’s perhaps the image Ethel’s mum has of her daughter. Her reality couldn’t be more different.

“I need help,” Ethel told the PIJ in the last of the interviews. “If I stay, I will die of depression.”

This story was produced by the Platform of Investigative Journalism and syndicated by the IJ Hub on behalf of its member centre network in Southern Africa.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.