How Illegal Mining Is Fueling an Illicit ARV Trade in Muchinga

By Linda Soko Tembo

From armed gangs at Kikonge gold mine in north-western Zambia to illicit antiretroviral drug sales in Muchinga Province, illegal mining has evolved into a breeding ground for parallel economies sustained by weak oversight. These shadow networks now endanger lives far beyond the mine pits.

An undercover investigation by MakanDay in Mpika and Shiwang’andu districts has found that antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), meant to be provided free of charge through Zambia’s public health system, are being sold illegally for cash in remote gold-mining camps in Muchinga.

The life-saving medicines, central to Zambia’s HIV response, are traded openly by unlicensed vendors in informal mining settlements. The practice exposes patients to treatment failure and drug resistance, while raising serious questions about drug diversion, regulatory breakdowns, and public-health safeguards.

In these isolated settlements, MakanDay documented the sale of ARVs and other essential medicines without prescriptions, clinical assessment, or proper storage, conditions health experts warn can undermine decades of progress in HIV treatment.

A new gold frontier, old governance gaps

Muchinga has rapidly emerged as one of Zambia’s newest gold frontiers, transforming once-quiet rural areas into sprawling, largely unregulated mining settlements. While the gold rush has created short-term livelihoods, it has also brought unsafe working conditions, environmental damage, rising crime, and now a dangerous illicit trade in life-saving medicines.

Following credible tip-offs, a MakanDay journalist travelled to Muchinga to verify claims that ARVs supplied through government health facilities were leaking into illegal mining areas. Because most mining camps lack formal health services and the allegations involved potential criminal conduct, the reporting was conducted undercover.

Inside Kanyelele mine

Kanyelele gold mine in Mpika was MakanDay’s first stop and is one of the largest informal mining sites in Muchinga Province. Although the mine is officially managed by the Learn to Share Cooperative, illegal mining continues openly alongside licensed operations.

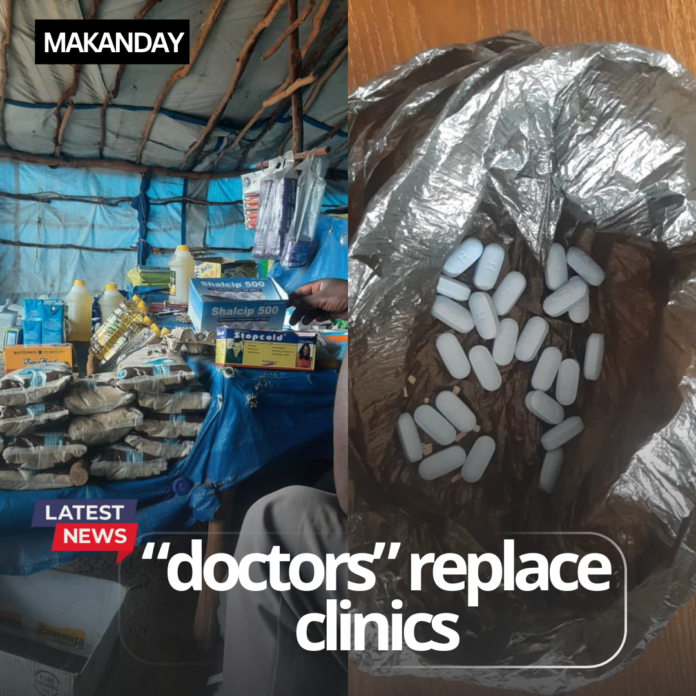

The sprawling camp has no clinic or health post, leaving thousands of illegal miners dependent on informal drug sellers for medical care. Operating from makeshift stalls and grocery shops, these sellers dispense medicines without training, licences, or oversight.

Among the drugs sold are painkillers, antibiotics, traditional remedies, and ARVs, which are legally available only through government health facilities.

To establish whether ARVs were being sold, the journalist posed as a patient who had run out of HIV medication. One trader, who sells groceries and medicines from a small shop near the mine, admitted that he had previously sold ARVs, though he said none were available at the time.

“I sell a one-month supply at K150,” he said. “I have contacts at Mutamba Health Post and Mpika Urban Clinic. Once I make those contacts, I can get the drugs.”

While the journalist was at the stall, a man seeking treatment for a severely swollen leg arrived. Without examining the patient or asking basic medical questions, “Doctor Panado” told the journalist the required medicine was not available and instructed him to return later that day, illustrating the dangerous and unregulated nature of healthcare in the camp.

Kanyelele Mine lies about 70 kilometres from Mpika town, off the Kasama–Mpika road, and is particularly difficult to access during the rainy season. When roads become impassable, motorcycles are often the only means of transport. This isolation effectively cuts the mining camp off from routine government inspections, creating conditions in which illegal trade, including in medicines, can thrive.

Danger Hill: medicine without oversight

At Danger Hill, off the Mpika–Chinsali road, an informal mining site in Mukwikile Chiefdom in Shiwang’andu district, access is so limited that routine government oversight is virtually non-existent. Reaching the site requires crossing streams on logs and navigating long stretches without roads or bridges, leaving communities cut off for weeks during the rainy season.

Despite the isolation, a thriving trade in medicines operates openly. Informal shops sell painkillers, antibiotics, family-planning drugs, and injectable contraceptives without prescriptions or medical supervision, pointing to a broader breakdown in pharmaceutical regulation beyond ARVs.

At one stall, a woman selling medicines said she did not stock ARVs but admitted that her drug supplies were collected by a relative who worked at a health facility. She said her uncle had travelled to Chinsali district to “pick drugs,” suggesting a direct link between public health facilities and the illegal supply of medicines to mining camps.

She openly listed her prices: family-planning pills sold at K40 per monthly strip and injectables at K60. There were no patient records, medical assessments, or safeguards, only cash transactions.

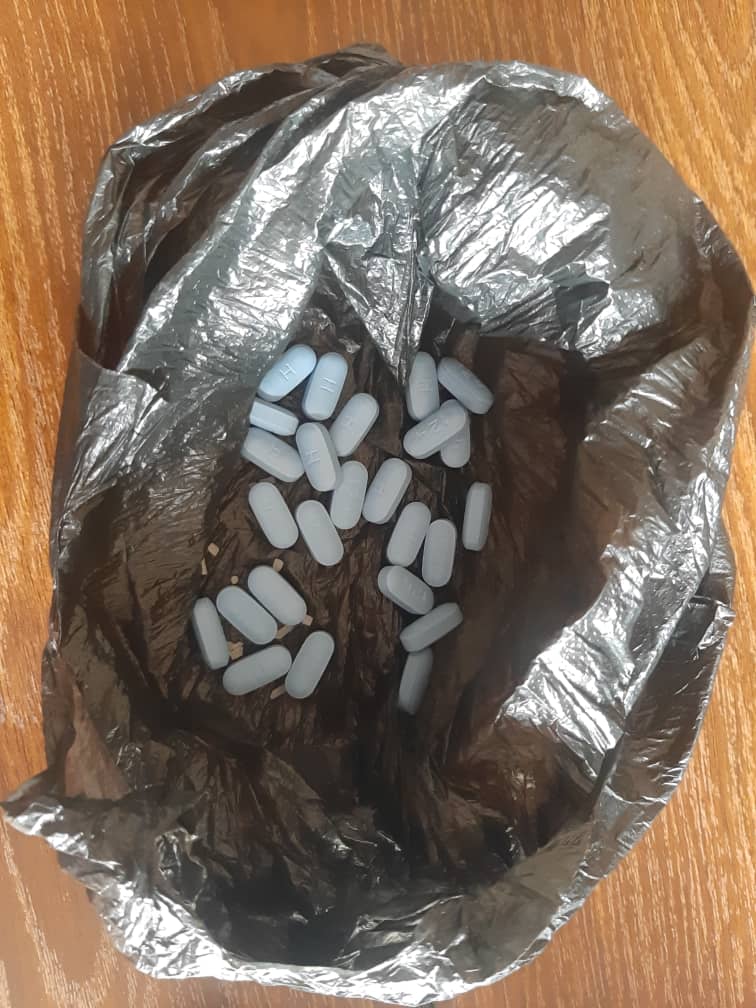

At another stall, a man known locally as “Dr. Mutale” confirmed that ARVs were available. After the journalist posed as a patient who had run out of medication, he supplied a one-month course of ARVs for K150.

He did not ask about the patient’s HIV regimen, request a health card, or verify treatment history. Instead, he wrapped the ARVs in a black plastic bag and handed them over.

When asked for proper packaging, “Dr. Mutale” said the bottle he had was meant for a six-month supply and could only be provided if the buyer paid K900. He said he was selling the drugs on behalf of a woman who supplied them, confirming the involvement of multiple intermediaries.

The ease with which ARVs were obtained at Danger Hill, without prescriptions, clinical oversight, or proper storage, points to the scale of regulatory failure in areas where health outreach and enforcement are absent.

Inside a public health facility

More significantly, it was established that ARVs were also being sold inside a public health facility in Mpika.

Posing as a patient who had run out of HIV medication, the journalist approached a health worker and requested ARVs. No proof of HIV status, treatment history, or referral documents were requested. After recording only a name and age, the health worker dispensed a one-month supply of ARVs for K150.

The price mirrored those documented in illegal mining camps, suggesting a direct and traceable link between public health facilities and the illicit resale of ARVs. The drugs were issued without counselling, regimen verification, or adherence checks, safeguards central to HIV treatment.

Several Mpika residents independently told MakanDay that obtaining medicines from public facilities for resale or private use is widely perceived as possible, reinforcing concerns that drug leakages are not isolated incidents.

Official denials, systemic gaps

During a provincial online meeting of health officials on January 12, following a Times of Zambia HIV story, authorities denied that health workers were involved in selling ARVs. Instead, they blamed patients, alleging that some individuals sell surplus ARVs received through multi-month dispensing.

MakanDay’s findings contradict that explanation. The sale of ARVs inside a public health facility, without verification or proper dispensing procedures, points to internal system failures rather than patient abuse alone.

A senior provincial health official, speaking on condition of anonymity, acknowledged that illegal mining has expanded rapidly without corresponding public-health planning.

“From a clinical care perspective, the biggest challenge is the supply chain,” the official said. “We are dealing with populations in illegal mining areas where no system was put in place to manage public-health commodities. That gap creates opportunities for abuse.”

The official said there is no effective system to track the movement of patients on ARVs or to monitor drug allocations at facility level in high-risk areas.

What the law says

Kandandu Chibosha, the Ministry of Health’s Chief Pharmacist for Rational Medicine Use said selling drugs outside licenced pharmacies and chemists is illegal.

He stressed that medicines in public health facilities, including ARVs, are paid for by the government and must be provided free of charge. Patients, he said, should never be asked to pay, regardless of distance or inconvenience.

Chibosha warned that buying ARVs from informal markets poses serious risks, including poor storage, reduced potency, treatment failure, and drug resistance. He cautioned against dispensing ARVs in plastic bags, noting that they are supplied in protective packaging to preserve quality.

People living with HIV, he said, should only access ARVs through authorised facilities, where the government provides multi-month dispensing of up to six months. Health workers found selling medicines risk dismissal.

Regulators unaware

Medicines in Zambia are regulated by the Zambia Medicines Regulatory Authority (ZAMRA). Yet despite these legal prohibitions and official assurances, MakanDay documented ARV sales both in illegal mining camps and inside a public health facility, raising questions about enforcement and internal controls within the health system.

ZAMRA told MakanDay it was not aware of reports of the illegal sale of drugs, including ARVs, in mining camps in Mpika and Shiwang’andu districts.

“I am not aware of such reports,” said Senior Public Relations Officer Ludovic Mwape. “We will call upon our enforcement wings to investigate the matter, after which I will be in a position to comment,” Mwape said.

A growing public-health risk

Health experts warn that without urgent audits of ARV stocks, tighter tracking of drug allocations, and swift disciplinary action, the illegal diversion of life-saving HIV medication is likely to persist, particularly in remote mining districts where oversight is weakest.

As illegal mining expands faster than health services and regulation can follow, experts warn that Zambia’s HIV response risks being quietly undermined, not by drug shortages, but by a parallel market thriving in the country’s blind spots.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.