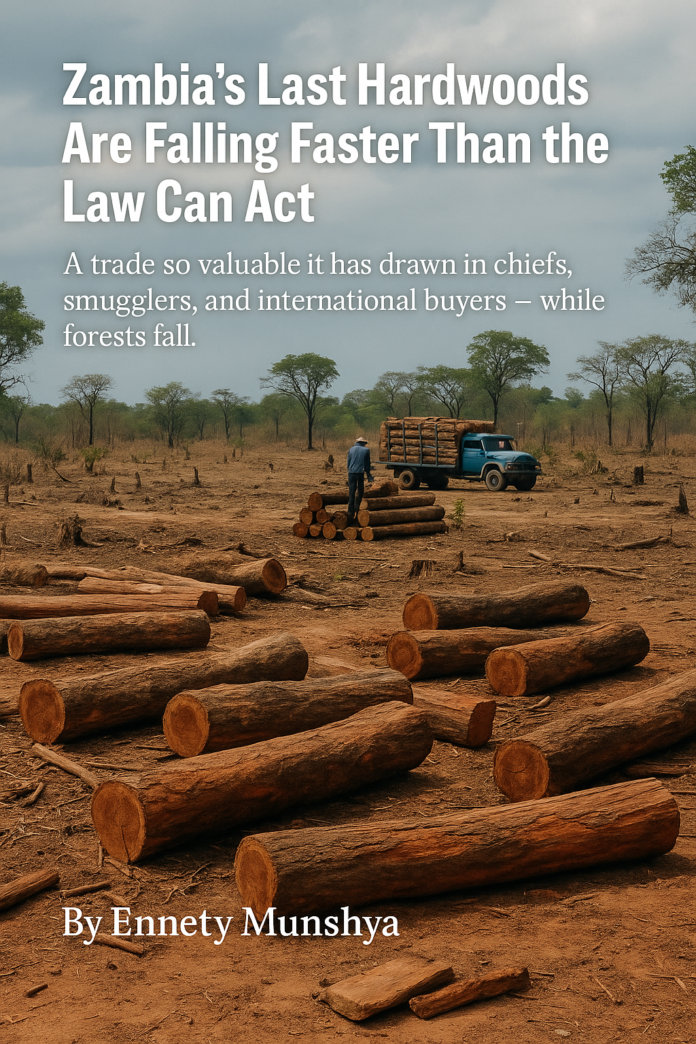

A trade so valuable it has drawn in chiefs, smugglers, and international buyers — while forests fall.

By Ennety Munshya

At sunrise in Kanjelebende village under Chief Mulilo in Chama District, eastern Zambia, the buzz of chainsaws now replaces birdsong. To many residents, it is the sound of a forest vanishing, and with it, a way of life.

Once-shaded fields now lie open and bare, where mopani and misimbiti hardwoods stood for generations. These trees are more than timber, they are medicine, firewood, fertile soil, rainfall, and heritage.

Yet they are being cut at a pace communities say they have never witnessed before — driven by foreign buyers, cross-border syndicates, and a trade so lucrative that even traditional leaders have been drawn into it.

And as the forests fall, Zambia’s laws, enforcement systems, and forest data are struggling to keep up.

According to a source involved in forest enforcement, the impact is already visible. Local temperatures are rising, soils are drying, and some tree species are nearing extinction. This aligns with findings by the World Resources Institute (WRI), a global research organisation focused on environmental protection.

“Removal of forest cover, especially in the tropics, increases local temperatures and disrupts rainfall patterns in ways that compound the local effects of global climate change, threatening severe consequences for human health and agricultural productivity,” the WRI notes in its 2022 report on the effects of deforestation on climate.

Logging in Chama communities is as old as the forests themselves. Here, many families rely on the forest economy for food, medicine, firewood, housing and other essential uses.

But MakanDay has found that the landscape is rapidly changing. Foreign loggers from neighbouring Tanzania and Malawi, often working hand in hand with locals, have moved in, exploiting the forests on a scale that residents say they have never witnessed before. Despite government efforts to regulate timber harvesting, enforcement remains weak, and illegal mining is further compounding the destruction.

Once cut, much of the timber is moved through informal bush routes into Tanzania. From there, Dar es Salaam, the country’s main commercial hub, acts as a major transit point. The logs are then exported in bulk to China, now the dominant buyer of Zambia’s hardwoods, according to sources familiar with the trade.

The extensive destruction of forests is not only fueled by economic pressures and poor oversight, community leaders such as chiefs, are also cashing in.

Last year, a chief was arrested for harvesting timber in a game management area (GMA).

Between 2010 and 2017, Zambia’s log exports surged by more than 6,000 percent. China alone accounted for 99 percent of the trade, underscoring the overwhelming dominance of a single foreign market over the country’s forestry sector. This is according to a 2021 report by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), which highlights the extent of the crisis.

Targeted species

The most targeted tree species in Chama include mopani, mupapa, and two high-value hardwoods locally known as misimbiti or African blackwood and leadwood. In Zambia, these misimbiti species grow naturally only in Chama district and in Sioma Ngwezi National Park in Western Province.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), African blackwood is already experiencing a significant population decline driven by rising international demand. The specie is highly valued for its dark, dense heartwood used in the production of musical instruments, fine carvings, and luxury craftwork. This premium market value has made African blackwood one of the most targeted species for illegal logging. Globally, it is listed as near threatened, narrowly avoiding classification as vulnerable under IUCN’s Criterion A for population reduction.

However, African blackwood is not the only misimbiti species at risk. Leadwood, which shares the same local name, is also under increasing pressure from uncontrolled harvesting, even though it is not currently listed as threatened on the IUCN red list. While the shared name can cause confusion, it also highlights a broader conservation problem: both species are in high demand and could face serious depletion if management and enforcement are not urgently strengthened.

“The misimbiti is very scarce but fetches a very high price, which is why most people are after it. They look for it like they are looking for a precious mineral. Tanzanians are the ones after it mostly,” the source said.

The arrest of Chief Chikwa — a sign of how deep the crisis runs

The pressure on misimbiti has reached such a scale that it is now drawing in foreign loggers, mostly from Tanzania, where the species has become almost depleted.

In late March 2024, Chief Chikwa of the Senga people in Chama District was arrested on allegations that he was harvesting timber in a Game Management Area (GMA).

Although early media reports alleged that the Chief was involved in harvesting timber within the GMA and transferring his licence to foreign companies, he denied the accusations when approached for comment by MakanDay.

“… the truth was that I had a timber licence in placed and those trees that were cut I bought from the forestry department,” he said. “The timber that is harvested is usually bought by anyone, the locals, including foreign nationals – Tanzanians and the Chinese.”

The involvement of foreigners underlines how deeply entrenched and lucrative the illegal hardwood trade has become, extending beyond small-scale cutters to include cross-border syndicates and high-value export markets.

Timber licencing and forest inventory

In September 2022, the Ministry announced that it had issued 190 timber concession licences in the small- and medium-scale categories countrywide, out of 483 applications received.

Zambia’s last comprehensive forest inventory was conducted between 2012 and 2014 under the Integrated Land Use Assessment (ILUA). To date, ILUA remains the most recent national reference for forest resource data. This means that current harvesting decisions are based on decade-old information, putting rare and slow-growing tree species at higher risk of depletion because many have not been formally listed as protected.

Legal framework and penalties

The Forests Act No. 4 of 2015 governs the management, protection and utilization of forest resources in Zambia.

However, a source familiar with forest enforcement said illegal logging persists partly because penalties under the Forests Act are far less punitive than those in the Wildlife Act.

“The penalties under the two laws differ sharply. Under the Forests Act, illegal loggers can pay fines ranging from about K15,000 to K60,000, while wildlife crimes attract fines of up to K180,000 or jail terms of up to seven years,” the source explained.

He added that these relatively low fines have made illegal logging a low-risk, high-return business for well-resourced traffickers.

“The people we arrest are just frontliners. The real owners of the business are in Dar es Salaam waiting for the consignments. They have the money and equipment. Local people only get peanuts. They cut our timber and it’s gone.”

Challenges in enforcement

A shortage of manpower, transport and operational resources within the forestry department continues to undermine effective monitoring and enforcement.

Brighton Nyimbili, chairperson of the Tiyeseko Community Forest Management Group, confirmed that illegal harvesting remains widespread and is largely driven by foreign buyers.

“Keep in mind that these people have the capacity to pay the fines. The ones we are arresting are just frontliners. The real owners are in Dar es Salaam, waiting for the consignments. They have the equipment; our locals only get peanuts from these dealings. They cut our timber and off they go,” the source added.

He added that community efforts to safeguard forests are constrained by the sheer size of the area: “The forests we are expected to protect cover about 19,000 hectares, but we do not have adequate transport or other patrol resources.”

19,000 hectares is equivalent to about 27,000 football pitches.

As night falls in Kanjelebende village, the sound of chainsaws fades into silence. But for communities who depend on the forest, the loss echoes long after the trees are gone.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.