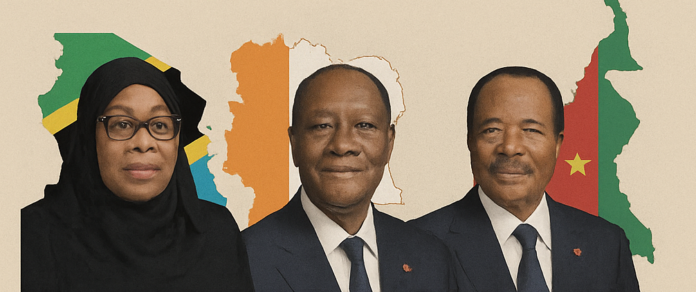

In October alone, three African countries, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and Tanzania, went to the polls. Yet in all three cases, voters appear to have chosen continuity over change, or, as some critics argue, never really had a choice at all.

In Tanzania, the general elections held on 29 October 2025 saw President Samia Suluhu Hassan retain power after her two biggest challengers were disqualified from the race. The move angered citizens and rights groups, who decried an intensifying crackdown on opposition members, activists, and journalists. The ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), extended its six-decade dominance through another sweeping victory.

In Côte d’Ivoire, President Alassane Ouattara secured a fourth term with roughly 90 percent of the vote in the 25 October 2025 election. Turnout hovered around 50 percent, well below previous levels. With major rivals such as Laurent Gbagbo and Tidjane Thiam barred from running, analysts described the outcome as a consolidation of power rather than a renewal of democracy.

In Cameroon, a presidential election on 12 October 2025 returned Paul Biya, now 92, to office with about 53 percent of the vote, continuing a rule that began in 1982. His main challenger, Issa Tchiroma Bakary, rejected the result, citing irregularities ranging from inflated voter registers to polling-station relocations. Protests followed, leaving at least four people dead and dozens arrested.

The Tanzanian election carries direct implications for Zambia and the broader SADC region. Tanzania is often viewed as a bellwether for political freedom in East Africa, and its shrinking democratic space could influence norms across the continent.

While opposition groups and citizens express frustration over the outcomes, what many Africans, including Zambians crave are not merely electoral victories but structural reforms, changes that strengthen institutions rather than personalities.

Across the continent, governments change hands, yet the machinery of power, the statecraft through which authority is acquired, protected, and manipulated, remains largely the same.

As one Tanzanian observer quipped, “Our opposition is like a Wi-Fi signal, it exists, but you can’t always connect”. The remark captures a deeper truth: opposition politics cannot be effective when the playing field is invisible or uneven.

Until opposition parties build credible platforms, and ruling elites respect the independence of institutions, Africa’s elections will remain elaborate rituals of continuity. True democracy will not come from the ballot box alone, but from the courage to reform the systems that keep it empty.

MakanDay

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.