In this report, Ennety Munshya exposes the human cost of a failing cancer care system—told through the real-life stories of patients and caregivers, many of them poor and from rural communities, who endure pain, worsening health, and death amid chronic delays, broken equipment, and broken promises.

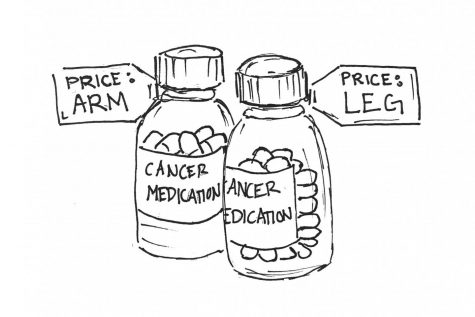

Zambia’s only public cancer facility, the Cancer Diseases Hospital (CDH) in Lusaka, is in crisis. The hospital is crippled by broken or outdated equipment, drug shortages, bureaucratic delays, and alleged corruption. The result is preventable patient deaths and widespread suffering.

In March 2024, the Zambian government signed a US$30.8 million contract with Siemens Healthineers to rehabilitate and re-equip CDH, the country’s only public cancer treatment centre.

The contract includes the decommissioning of obsolete equipment, structural rehabilitation, and the installation of modern medical machinery—such as four linear accelerators, two brachytherapy units, two CT simulators, an MRI machine, and a mammography unit.

Failed referral plans

In October 2023, then Health Minister Sylvia Masebo announced that radiation patients would be sent to Tanzania during renovations. The plan failed. India was later named as the new referral destination, but many patients report bribery, false promises, and uncertainty surrounding access.

It is hoped that, once completed, these high-profile upgrades at the cancer hospital will bring much-needed relief to patients—many of whom are poor and from rural areas—who continue to endure prolonged pain, worsening health, and even death as a result of the system’s ongoing failures.

Human cost – a mother’s tragedy

A woman recounts how her mother died of cervical cancer after waiting months for treatment at CDH and paying K6,000 in a bribe for a referral to India that never materialised.

Her mother was diagnosed with cervical cancer in October 2023, after experiencing abdominal pains and irregular discharge. Concerned about her symptoms, she went for a check-up at Livingstone General Hospital, where doctors suspected cervical cancer.

The hospital referred her to a private laboratory for a biopsy, which confirmed that the cancer was at Stage 2B – meaning the cancer had spread beyond the original site. She was then referred to the Cancer Diseases Hospital in Lusaka for specialised treatment.

“By the time of her diagnosis, she was very okay, and we were hopeful that once she went to Lusaka for treatment, everything would be fine,” the daughter recalls.

Their first visit to Lusaka was in November 2023.

“The hospital opened a file for her, did some tests, and gave her painkillers. She was told to return in January 2024 for a review,” she said.

However, in January, they were again told to come back in March.

“During the January visit, I tried to engage someone to help speed up the process. Through a connection, more tests were done, and a doctor recommended that my mother undergo radiotherapy. But I was told the treatment was not available at the hospital—she would have to go to India,” she explained.

By May, her mother’s health had worsened. While at the hospital registry, the daughter said a woman approached her, offering to help get her mother’s name on the list of patients being sent to India for treatment.

“She told me I needed to pay her K6,000 for a recommendation letter to be written and signed by the doctor. She assured me my mom would travel to India within two weeks. I accepted, because I was desperate.”

Her mother remained in Lusaka, waiting for the promised letter—but it never came. Eventually, she returned to Livingstone.

A month later, after constant follow-ups with the woman from CDH, she was advised to bring her mother back to Lusaka for chemotherapy while they continued waiting for the India trip.

“We took her back to CDH, but chemotherapy couldn’t be done because her hemoglobin levels were too low. She was given medication to take for two weeks to help boost her blood levels.”

When they returned to the hospital, they were told the cancer had progressed to Stage 4 and had spread to her kidneys. At that point, the doctors said there was nothing more they could do.

“She was told to go back home. That was the worst period of her life. She lost all hope. She even stopped taking her herbal medicine. It was as though she had accepted that she was going to die.”

In August 2024, her mother was admitted to Livingstone Central Hospital after experiencing vomiting and diarrhea. She was discharged after three days, but her condition continued to deteriorate.

“She became very sick. Even opening her mouth to eat or drink was a problem. We just started praying for a miracle.”

Two weeks later, she experienced heavy vaginal bleeding, which led to her death. She was pronounced dead upon arrival at the hospital.

“Thinking about the queue—it’s very unfortunate that just to be put on that list, you have to bribe someone. It’s sad that Zambians can’t get that treatment locally. I think it would even be cheaper for the government to procure the necessary machines to provide the treatment here, rather than sending patients abroad. My mother’s cancer advanced from Stage 2B to Stage 4 in just ten months,” she explained.

Over the past three months, a MakanDay journalist has been visiting the Cancer Diseases Hospital, speaking with patients and their caregivers.

Many reported being given multiple hospital appointments—often without receiving any actual treatment.

One patient, who requested anonymity for fear of victimisation during future visits, revealed that she was diagnosed with stage 2B cervical cancer in July last year.

She also said that the hospital staff informed her she would be placed on a list of patients being considered for treatment in India. However, she’s uncertain when or if that will happen.

“I don’t think it’s even easy to get on that list. They keep giving me new appointment dates, but nothing is ever done. I’m always sent back home. I’m in pain and surviving on painkillers,” she narrated.

Esnart Nyendwa a care giver has told MakanDay that the processes are very slow at the hospital.

“I have been bringing my husband here for the past five months but every time we come we are given a new date. Some tests were conducted but up to now we don’t know the results. We had an appointment to see the doctor today, we came here at 08:00hrs but this is 12:00hrs we have not been attended to,” she said.

The Zambian Cancer Society (ZCS), a non-profit, says CDH in Lusaka was a major step forward but is now overwhelmed and under-equipped.

ZCS Communications and Administration Manager, Idah Phiri, called for urgent investment, proper National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIMA) coverage for cancer treatment, and stakeholder collaboration to prevent more deaths.

Zambia has only one hospital providing comprehensive cancer care for its population of nearly 20 million. A second facility is under construction in Ndola, Copperbelt Province, and is nearing completion, with equipment already beginning to arrive.

The existing hospital, located within the University Teaching Hospital grounds in Lusaka, opened in July 2006 and was officially inaugurated on 17th July 2007.

Prior to the construction of the hospital, the government sent cancer patients abroad at a cost of US$10,000 per patient. This expense has likely increased since then.

Due to limited budget allocations for treatment abroad, only 350 cases out of 5,000 were sent between 1995 and 2004.

Lack of transparency

On July 9, 2025, MakanDay requested for official data from the Cancer Diseases Hospital on how many patients have been referred to India for treatment, criteria for selection, cancer death rates, and the extent of coverage under NHIMA. As of the day of publication, the hospital has not responded.

Discover more from MAKANDAY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.